ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use for people with inflammatory breast cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for inflammatory breast cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How inflammatory breast cancer is treated

In cancer care, doctors specializing in different areas of cancer treatment work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, genetic counselors, nutritionists, and others.

Inflammatory breast cancer is considered a locally-advanced breast cancer and is typically treated with several types of treatment, including chemotherapy, surgery, radiation therapy, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) targeted therapy, and/or hormone therapy, as appropriate.

Inflammatory breast cancer treatment usually starts with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy before surgery is called neoadjuvant therapy or preoperative therapy. After chemotherapy, people with inflammatory breast cancer usually have surgery to remove the breast. Then, they receive radiation therapy to the chest wall and the nearby lymph nodes. If a patient has metastatic (stage IV) breast cancer when first diagnosed, the main treatment options are systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy. Surgery and/or radiation therapy are less commonly used.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the type and stage of cancer, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for inflammatory breast cancer because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

The common types of treatments used for inflammatory breast cancer are described below. Your care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care.

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body. This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications to take at home, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for inflammatory breast cancer include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunotherapy

-

Hormonal therapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen consists of a specific treatment schedule of drugs given at repeating intervals for a set number of times. Chemotherapy for inflammatory breast cancer is usually given before surgery, called preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sometimes additional chemotherapy is also given after chemotherapy, called adjuvant chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy for inflammatory breast cancer that has not spread outside of the breast and regional lymph nodes usually includes a combination of drugs.

Common drugs for non-metastatic inflammatory breast cancer may include:

-

Capecitabine (Xeloda)

-

Carboplatin (available as a generic drug)

-

Cyclophosphamide (available as a generic drug)

-

Docetaxel (Taxotere)

-

Doxorubicin (available as a generic drug)

-

Epirubicin (Ellence)

-

Fluorouracil (5-FU)

-

Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall)

-

Paclitaxel (Taxol)

-

Protein-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane)

Common chemotherapy combinations for inflammatory breast cancer may include:

-

AC or EC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide or epirubicin and cyclophosphamide) followed by T (paclitaxel or docetaxel)

-

TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide)

Other chemotherapy combinations that may be used for inflammatory breast cancer include:

-

AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide)

-

CAF (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU)

-

CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-FU)

-

CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU)

-

EC (epirubicin and cyclophosphamide)

-

TC (docetaxel and cyclophosphamide)

Treatments that target the HER2 receptor may be given with chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer (see "Targeted therapy," below).

Immunotherapy may be given with chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer (see "Immunotherapy," below).

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual and the drug and dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, numbness and tingling in the fingers and toes, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea or constipation. These side effects usually go away after treatment is finished. Long-term side effects may occur, such as nerve damage or fatigue, and, rarely, heart damage or secondary cancers.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

You can learn more about drugs used to treat metastatic inflammatory breast cancer in the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. These treatments are very focused, and they work differently than chemotherapy. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all cancers have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in the cancer. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

HER2 is a specialized protein found on breast cancer cells that controls cancer growth and spread. If an inflammatory breast cancer tests positive for HER2, targeted therapy will likely be an option for treatment along with standard chemotherapy.

HER2-positive inflammatory breast cancer is usually treated with medications that target HER2. The choice of which HER2-targeted drug to use depends on the cancer’s stage.

Commonly used HER2-targeting medications for breast cancer include:

-

Trastuzumab (Herceptin, Herzuma, Ogivri, Ontruzant, Hylecta)

-

Pertuzumab (Perjeta)

-

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla)

-

Neratinib (Nerlynx)

HER2-targeted therapy is usually given in combination with chemotherapy, and then after chemotherapy ends. Common combination regimens for HER2-positive inflammatory breast cancer include:

-

AC-THP (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

-

TCHP (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

Other combination regimens that may be used for HER2-positive inflammatory breast cancer include:

-

AC-TH (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, trastuzumab)

-

TCH (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab)

If a patient has no cancer still remaining in the breast at the time of surgery, they will generally be recommended to continue to receive trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab every 3 weeks until completion of 1 year of therapy (11 to 14 doses). However, if a patient is found to have cancer still remaining in the breast at the time of surgery, they will generally be recommended to receive ado-trastuzumab emtansine every 3 weeks for 14 doses.

Patients receiving HER2-targeted therapy have a small risk of developing heart problems. This risk is increased if they also have other risk factors for heart disease. Heart problems do not always go away, but they are usually treatable with medication. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for a specific medication and how they can be managed.

Bone modifying drugs

Bone modifying drugs block bone destruction and help strengthen the bone. They may be used to prevent cancer from recurring in the bone or to treat cancer that has spread to the bone. Bone modifying drugs are not a substitute for standard anti-cancer treatments. Certain types of bone modifying drugs are also used in low doses to prevent and treat osteoporosis, which is the thinning of the bones.

The drugs used to block bone destruction and present breast cancer recurrence in the bone are:

All people with breast cancer who have been through menopause, including people with inflammatory breast cancer, should have a discussion with their doctor whether bisphosphonates are right for them. Several factors affect this decision, including your risk of recurrence, the side effects of treatment, the cost of treatment, your preferences, and your overall health.

If treatment with bisphosphonates is recommended, ASCO recommends starting within 3 months after surgery or within 2 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. This may include treatment with clodronate (multiple brand names), ibandronate (Boniva), or zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa). Clodronate is not available in the United States.

This information is based on the ASCO and Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) guideline, “Use of Adjuvant Bisphosphonates and Other Bone-Modifying Agents in Breast Cancer.” Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Other types of targeted therapy for breast cancer

You may have other targeted therapy options for breast cancer treatment, depending on several factors. The following drugs are used for the treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer in people with an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation and a high risk of breast cancer recurrence.

-

Olaparib (Lynparza). This is a type of oral drug called a PARP inhibitor, which destroys cancer cells by preventing them from fixing damage to the cells. ASCO recommends using olaparib to treat early-stage, HER2-negative breast cancer in people with an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation and a high risk of breast cancer recurrence. Adjuvant olaparib should be given for 1 year following the completion of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy (if needed).

-

Abemaciclib (Verzenio). This oral drug, called a CDK4/6 inhibitor, targets a protein in breast cancer cells called CDK4/6, which may stimulate cancer cell growth. It is approved as treatment in combination with hormonal therapy (tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor; see "Hormonal therapy" below) to treat people with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early breast cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes and has a high risk of recurrence. ASCO recommends consideration of 2 years of treatment with abemaciclib combined with 5 or more years of hormonal therapy for patients meeting these criteria, including for people whose cancer has a Ki-67 score higher than 20% (see Diagnosis). Treatment should be given following the completion of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy.

You can learn more about drugs used to treat metastatic inflammatory breast cancer in the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells. The following drug can be used in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of inflammatory breast cancer that is triple negative.

-

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This is a type of immunotherapy that is approved by the FDA to treat high-risk, early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer in combination with chemotherapy before surgery. It then is given alone following surgery.

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include skin rashes, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight changes. Other severe but less common side effects can also occur. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects of the immunotherapy recommended for you. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy, also called endocrine therapy, is an effective treatment for breast cancer that tests positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors (called ER positive or PR positive; see Introduction) in all stages of breast cancer. This type of breast cancer uses hormones to fuel its growth. Blocking the hormones may slow the growth of the cancer and destroy the cancer cells. Hormone therapy is typically recommended for hormone receptor-positive cancer after chemotherapy and radiation therapy or as treatment for metastatic breast cancer.

Hormonal therapy is usually taken for at least 5 years. It may be taken for up to 10 years, especially when there is a higher risk of the cancer returning. How long to continue hormonal therapy depends on the stage of cancer, the risk of it returning, and any side effects you are experiencing.

Hormonal therapy for inflammatory breast cancer is typically started either during or after adjuvant radiation therapy (see below). Hormonal therapy options include:

-

Tamoxifen (available as a generic) blocks estrogen from binding to breast cancer cells. It is a hormonal therapy that can be used before or after menopause.

-

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs, all available as generics) decrease the amount of estrogen made by the body. These drugs include anastrozole (Arimidex), exemestane (Aromasin), and letrozole (Femara). AIs are effective in treating breast cancer in postmenopausal people or premenopausal people who are also receiving ovarian suppression.

-

Ovarian suppression refers to the use of drugs or surgery to stop the ovaries from producing estrogen. It may be used in addition to another type of hormonal therapy for people who have not been through menopause. There are 2 methods used for ovarian suppression:

-

Drugs called gonadotropin or luteinizing releasing hormone (GnRH or LHRH) analogs that stop the ovaries from making estrogen. Goserelin (Zoladex) and leuprolide (Eligard, Lupron) are GnRH and LHRH agonists that stop the ovaries from making estrogen for 1 to 3 months.

-

Surgery to remove the ovaries, which permanently stops estrogen production.

Side effects of hormonal therapy can include hot flashes, decreased sexual desire or ability, body aches and stiffness, and mood swings. Find additional information about hormone therapy in the breast cancer treatment section. Learn more about the basics of hormone therapy.

Return to top

Surgery

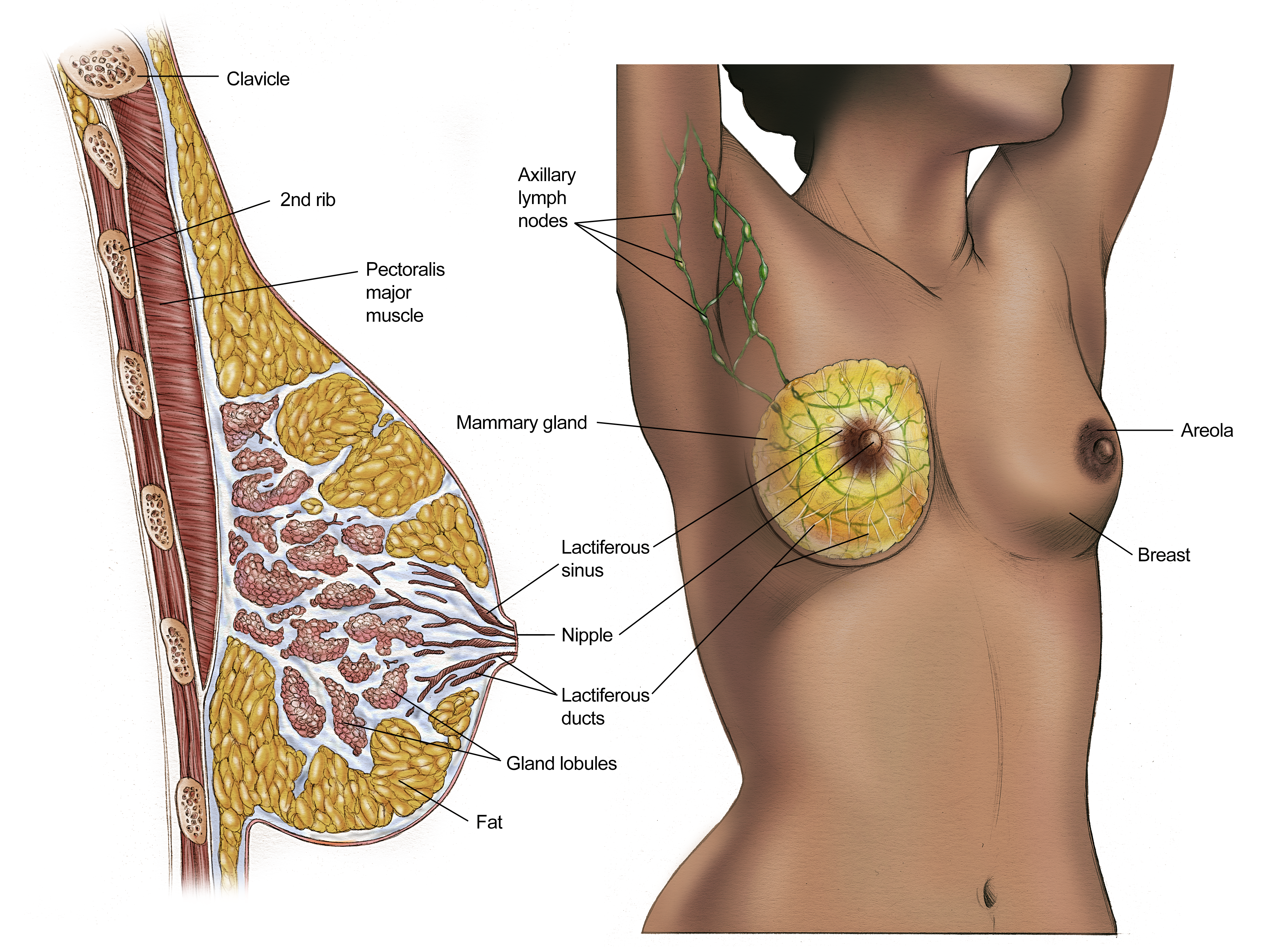

Surgery for breast cancer involves the removal of the tumor in an operation. Surgery is also used to examine the surrounding axillary or underarm lymph nodes. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer using surgery.

Because inflammatory breast cancer is usually located throughout the breast and the lymphatic vessels in the skin, starting with surgery first may not be successful to remove all of the cancer with negative margins. A negative margin means that there is no cancer left at the edges of the tissue removed during surgery. Any cancer left behind during surgery increases the chances of recurrence in the breast and affects healing. Because of this, chemotherapy is typically given first for inflammatory breast cancer to shrink and destroy the cancer in the breast, improving the chance that surgery will be successful.

The usual surgical treatment for inflammatory breast cancer is the removal of the entire breast, a procedure called a mastectomy. Reconstructive surgery of the breast after mastectomy is discussed below.

Before surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Lymph node removal and analysis

It is important to find out whether any of the lymph nodes near the breast contain cancer. This information is used to determine treatment and prognosis.

-

Sentinel lymph node biopsy. In a sentinel lymph node biopsy, the surgeon finds and removes a small number of lymph nodes from under the arm that receive lymph drainage from the breast. The pathologist then examines these lymph nodes for cancer cells. In general, a sentinel lymph node biopsy is not appropriate for inflammatory breast cancer, and an axillary lymph node dissection is preferred (see below).

-

Axillary lymph node dissection. In an axillary lymph node dissection, the surgeon removes many lymph nodes from under the arm. Then, a pathologist examines these lymph nodes for cancer cells. The actual number of lymph nodes removed varies from person to person. An axillary lymph node dissection is the preferred way to evaluate the axillary lymph nodes of a person with inflammatory breast cancer.

Reconstructive or plastic surgery

After a mastectomy, a patient may wish to consider breast reconstruction, which is surgery to rebuild the breast. Breast reconstruction is performed by a reconstructive plastic surgeon.

There are many methods to reconstruct the breast. It may be done with tissue from another part of the body or with synthetic or artificial implants. Certain options may be preferred for inflammatory breast cancer because radiation therapy (see below) is almost always needed. Talk with your doctor for more information and learn more about reconstruction options.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body.

A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time. Adjuvant radiation therapy is radiation treatment after surgery. It is effective in reducing the chance of breast cancer returning in both the breast and the chest wall. Adjuvant radiation therapy is nearly always recommended for people with inflammatory breast cancer after mastectomy because of the high risk of cancer cells remaining in the chest wall.

Standard radiation therapy after a mastectomy is given to the chest wall for 5 days (Monday through Friday) for 5 to 6 weeks.

Standard radiation therapy after a lumpectomy is external-beam radiation therapy given daily. This usually includes radiation therapy to the whole breast for several weeks, depending on whether the cancer had spread to the lymph nodes. It is then followed by a more focused treatment to the area where the tumor was located in the breast for the remaining treatments. This focused part of the treatment, called a boost, is standard for people with invasive breast cancer to reduce the risk of a recurrence in the breast.

If there is evidence of cancer in the underarm lymph nodes, radiation therapy may also be given to the lymph node areas in the neck or underarm near the breast or chest wall. There has been growing interest in newer radiation regimens to shorten the length of treatment from 6 to 7 weeks to 3 to 4 weeks. However, these regimens have not been studied in people with inflammatory breast cancer. As always, talk with your doctor about your options for radiation therapy, as well as the risks and benefits of these options.

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, including fatigue, swelling of the breast, and skin changes. Skin changes may include redness, discoloration, and pain or burning, sometimes with blistering or peeling. Very rarely, a small amount of the lung can be affected by the radiation, causing pneumonitis, a radiation-related inflammation of the lung tissue. This risk depends on the size of the area that received radiation therapy. However, this tends to heal with time. In the past, with older equipment and radiation therapy techniques, people who received treatment for breast cancer on the left side of the body had a small increase in the long-term risk of heart disease. Modern techniques are now able to spare most of the heart from the effects of radiation therapy.

Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative care or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to get rid of the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Metastatic inflammatory breast cancer

If cancer has spread to another part in the body from where it started, it is called metastatic cancer. If this happens, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have experience in treating it. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan. Clinical trials might also be an option. Learn more about getting a second opinion before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan.

Your treatment plan may include a combination of the treatments discussed above, or additional treatment options that are only used to treat metastatic breast cancer. However, surgery and radiation therapy may be used more often to manage symptoms in other parts of the body than to treat the cancer. Palliative care will also be important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

For most people, a diagnosis of metastatic cancer is very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of your health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program.

Return to top

Finishing treatment and the chance of recurrence

For patients with stage III inflammatory breast cancer, when treatment ends, a period many call "post-treatment survivorship" begins. After treatment, people can feel uncertain and worry that the cancer may come back. While many patients never have the disease return, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (locoregional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence or metastatic disease).

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatment types described above, such as chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent inflammatory breast cancer. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from breast cancer is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the goals of care may switch to focusing on helping a person live as well as possible with the cancer.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer may be difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable and emotionally supported is extremely important.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.