ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different treatments doctors use for people with cancer of unknown primary (CUP). Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for CUP. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option to for all stages of cancer. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

Planning treatment for CUP

In cancer care, different types of doctors often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams also include a variety of other health care professionals, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, and others.

To figure out the best treatment plan for CUP, doctors rely on the answers to the following questions:

-

Was the primary site found during clinical and imaging testing? If so, treatment should follow guidelines for an advanced (metastatic) tumor of that primary tumor type.

-

Did the pathologist identify a primary tumor or a specific tumor type, such as lymphoma or germ cell tumor? If so, treatment should follow guidelines for the specific tumor type.

-

If no primary site was found, does this CUP fit into any of the subgroups for which specific treatment is recommended? (See Subtypes.)

-

If no primary site was found and this CUP does not fit into any of the specific subgroups, can the site of cancer origin be predicted by molecular testing of the cancer biopsy sample? If so, should treatment be based on the tumor type predicted by the molecular cancer classifier assay, or should it be treated with an empiric (general) chemotherapy program (see below)?

-

Are any targeted treatments, as identified by comprehensive molecular profiling of the cancer (see below), likely to be helpful?

How CUP is treated

Because CUP has usually spread to at least 1 place when diagnosed, this type of tumor can rarely be removed by surgery or treated with localized radiation therapy. Therefore, chemotherapy is the most common treatment for CUP. Chemotherapy may be able to completely get rid of some tumors.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the type and stage of cancer, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for CUP because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

For many patients, a diagnosis of CUP can be very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of the health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program.

The common types of cancer treatments for CUP are described below. This section is followed by an outline of treatment for each of the recognized CUP subgroups, listed below. Finally, treatment options are outlined for patients whose clinical features do not fit into any of the recognized subgroups.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time. The chance that chemotherapy will be effective depends on the cancer type and location, the number of metastases involved, and the person's overall health. The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual as well as the drugs and doses used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These side effects usually go away after treatment has finished. Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body. When radiation treatment is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy.

Side effects from radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished. Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer using surgery. The extent and location of the surgery depends on where the cancer is found and its size.

Before surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment using drugs that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

A number of targeted cancer therapies are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat specific types of cancer. Although none of these drugs are currently approved to treat CUP, being able to accurately predict where a CUP started may also help identify a targeted drug that could be beneficial. For example, if a CUP is thought to have started in the lung, it may respond to a targeted therapy currently approved for lung cancer.

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for a specific medication and how they can be managed. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Return to top

Hormone therapy

The goal of hormone therapy is to alter the activity of hormones in the body, usually by trying to lower their levels or block their actions. Hormone therapy may be given to help stop a tumor from growing or to relieve symptoms caused by the tumor. This type of treatment may be an option for people in specific CUP subgroups (see below).

The side effects of hormone therapy depend on the specific type prescribed, so talk with your health care team about potential side effects. Learn more about the basics of hormone therapy.

Return to top

Treatment options for specific CUP subgroups

One of the following subgroups may be identified in 35% to 40% of patients during the initial clinical and pathologic evaluation. They each have specific treatment options that are often recommended.

-

Women with adenocarcinoma located only in the axillary lymph nodes. Treatment usually follows the guidelines for stage II breast cancer, even if no primary site in the breast can be found. Local treatment includes surgical removal of the breast (mastectomy) or surgical removal of the lymph nodes (axillary node dissection) plus radiation therapy to the breast. Chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and/or HER2-targeted therapy may be recommended after surgery, depending on the number of lymph nodes with cancer as well as the estrogen/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) status, HER2 status, and other molecular features of the tumor.

-

Women with peritoneal carcinomatosis, which is adenocarcinoma on the surface of the abdominal cavity. Treatment usually follows the guidelines for stage III ovarian cancer, even for women with healthy ovaries or whose ovaries have been removed. Whenever possible, surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible, known as debulking surgery, should be performed. Chemotherapy with a taxane/platinum combination, which is used in the treatment of ovarian cancer, is recommended after surgery. CA-125 is often a useful tumor marker blood test for monitoring how well treatment is working. About 20% to 25% of patients in this subgroup live for a long time after receiving treatment.

-

Young men with poorly differentiated carcinoma found in the mediastinum (center of the chest between the lungs) or retroperitoneum (back of the abdominal cavity). Some men in this group may have a germ cell tumor, even if the diagnosis cannot be made by the pathologist. High levels of HCG and AFP in the blood strongly suggest a germ cell tumor. People in this subtype usually receive chemotherapy according to the guidelines for the treatment of later-stage testicular cancer. After chemotherapy, surgery to remove any remaining cancer is often needed. This treatment approach is curative in about 30% of men in this group.

-

Squamous cell carcinoma in the cervical (neck) lymph nodes. Even if a primary site in the head and neck is not found after a careful search, people with tumors in this subgroup generally receive treatment according to the guidelines for locally advanced head and neck cancer. This usually includes radiation therapy and chemotherapy given at the same time. If small amounts of tumor remain in the cervical lymph nodes after radiation and chemotherapy, surgical removal of lymph nodes may add to the success rate of treatment. About 40% to 60% of people with this diagnosis live a long time after treatment.

-

Squamous cell carcinoma in the inguinal (groin) lymph nodes. Treatment generally includes surgical removal of all inguinal lymph nodes or radiation therapy. The doctor may recommend combining chemotherapy with radiation therapy.

-

Patients who have only a single metastasis. This group includes a broad range of patients, since the single metastasis (1 tumor) may be found in any part of the body, such as the lymph nodes, brain, lung, or liver. Depending on the location, treatment usually includes either surgical removal of the tumor or radiation therapy. Most people eventually develop metastases in other parts of the body, but this sometimes occurs after a long time without any disease.

-

Men with adenocarcinoma metastases only in the bones and/or an elevated PSA level. Treatment for this subtype usually follows the guidelines for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Hormone therapy, also called androgen deprivation, often causes long remissions. A remission is the disappearance of the signs and symptoms of CUP.

-

Patients with adenocarcinoma in the liver and/or abdomen. For tumors that have only spread in the abdomen, special pathology tests (IHC stains or molecular tumor profiling) sometimes suggest that the cancer started in the colon. These tumors are usually treated according to the guidelines for later-stage colon cancer, even if a primary site cannot be located with a colonoscopy.

-

Patients with adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma in the chest (mediastinum or lymph nodes). For cancers that have spread in the chest, special pathology tests (IHC or molecular profiling) sometimes suggest that the cancer started in the lungs. These cancers are usually treated according to guidelines for later-stage non-small cell lung cancer, even if the primary site cannot be found in the lungs.

-

Patients with pathology findings suggesting kidney cancer. In some people, specific pathologic findings (adenocarcinoma or clear cell histology, specific IHC staining, and/or molecular profiling) suggest that the cancer started in the kidney. People with these findings are usually treated according to guidelines for later-stage kidney cancer, even if no tumors are found in the kidneys.

-

Patients with adenocarcinoma or papillary carcinoma and metastases in the cervical (neck) lymph nodes. Though uncommon, people who show these features at diagnosis should be evaluated for thyroid cancer. Elevated serum levels of thyroglobulin or positive IHC staining for thyroglobulin in the cancer biposy is evidence that the cancer started in the thyroid. Treatment should follow guidelines for papillary/follicular thyroid cancer, even if no tumors can be found in the thyroid gland.

-

Patients with poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Although the primary site is usually not found, these types of neuroendocrine tumors often respond to chemotherapy with platinum/etoposide (Etopophos). This treatment can effectively shrink the cancer and improve cancer-related symptoms about 60% of the time. About 10% to 15% of people experience a complete remission with chemotherapy, and some live for a long time after treatment.

-

Patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Most well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, such as neuroendocrine tumors of the GI tract or neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, begin in the intestinal tract or pancreas. For cancers with an unknown primary site, the metastases are usually found in the liver. It is usually easy for the pathologist to tell the difference between well-differentiated and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. This distinction is important because the chemotherapy recommended for poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors is usually not effective for well-differentiated tumors. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors usually grow slowly, and patients often live for several years, even without treatment. In general, the treatment follows the guidelines for advanced neuroendocrine tumors arising in the gastrointestinal tract (carcinoid tumors) or pancreas.

All people with CUP are encouraged to talk with their doctor about participating in a clinical trial that is evaluating a new approach to treatment. In addition, talk with your doctor about the possible side effects and goals of each treatment option.

Return to top

Treatment for those not in a specific CUP subgroup

About 60 to 65% of all people with CUP do not have the characteristics of any of the specific subgroups described above. Most of the patients in this group have adenocarcinoma or poorly differentiated carcinoma (see Subtypes). The success of treatment for this group varies widely. Many of these patients have cancer that is resistant to treatment. However, others experience significant benefits from treatment.

The recommendations for treatment are in the process of changing based on ongoing scientific research. Until recently, the standard treatment for CUP focused on an approach called "empiric chemotherapy." Empiric chemotherapy uses a combination of drugs known to work against a variety of cancers.

In the past, many types of cancers were treated in similar ways, so empiric chemotherapy offered the best chance of success in many cases. Only about 5% of patients are cured with empiric chemotherapy, but it can shrink tumors in 35% to 40% of patients. Around 20% to 25% of patients who receive this treatment live for at least 2 years after diagnosis.

Important improvements have been made in the treatment of many types of cancer during the last 15 years. Many of the drugs responsible for these improvements are called targeted therapies (see above). Unlike traditional chemotherapy, targeted drugs work best for cancer with specific tumor features. For example, a drug that targets a mutation specific to lung cancer may not work at all for colon cancer, and vice versa. Another type of drug therapy called immunotherapy is a treatment that stimulates the immune system to attack cancer cells. It works well for some cancer types (e.g. lung, kidney), and less well for others. For these reasons, designing the most effective treatment for a patient with CUP is very difficult if the primary site is unknown.

However, new diagnostic tests can help predict the primary site for people with CUP, even when the primary site cannot be found. These tests are called molecular cancer classifier assays or gene expression profiling. Pathologists perform these new tests on tumor tissue taken during a biopsy. More and more scientific evidence shows that, in most cases, the predictions from these assays are accurate.

Researchers continue to compare treatments directed toward a specific tumor type, as predicted by these tests, and empiric chemotherapy. Some preliminary conclusions from clinical trials that have been completed can guide treatment. If the cancer is predicted to be a treatment-resistant tumor, such as pancreatic cancer or biliary cancer, site-specific treatments and empiric chemotherapy have similar outcomes. If the cancer is predicted to be a treatment-sensitive type (colorectal, breast, ovarian, lung, and other cancers), then site-specific treatment appears better than empiric chemotherapy. As an example, a patient predicted to have a cancer that started in the colon would benefit more from a treatment plan designed for later-stage colon cancer than from empiric chemotherapy. This treatment plan would include chemotherapy, targeted therapies and, in some cases, immunotherapy developed specifically for colon cancer.

Comprehensive molecular profiling

Many of the new drugs being developed to treat cancer are targeted therapies. These drugs work only when the cancer has specific molecular abnormalities, also called mutations or alterations. Many of these drugs are effective regardless of the cancer type, as long as the molecular abnormality is present. Specific molecular alterations in the tumor can also predict the efficacy of immunotherapy. Treatment with drugs based on molecular abnormalities in the cancer, rather than the site of the tumor origin, is called tumor agnostic treatment.

Comprehensive molecular profiling (CMP) is a test performed on cancer tissue from a biopsy to find out whether any molecular abnormalities are present that can be targeted with specific drugs. Treatment with drugs identified in this way has been very successful for other cancer types. Although experience in CUP is still limited, it appears that molecular abnormalities that can be targeted with drugs are present in up to 20% of CUP cases and that the use of appropriate targeted drugs is effective for these patients.

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. And, a diagnosis of CUP can bring additional challenges with its uncertainty about finding the primary site. Managing all of these effects is called palliative or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to get rid of the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy.

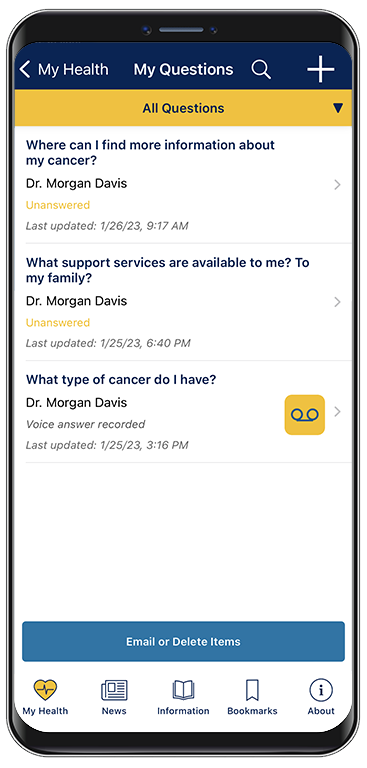

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED. For patients with CUP who receive chemotherapy and experience remission, treatment is usually stopped after 4 to 6 months.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after chemotherapy or other treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place or in other areas of the body. If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options.

Chemotherapy will usually be recommended, either with the same drugs you received before or with a new combination. If your first treatment was based on the tumor type predicted by gene expression profiling, second-line treatment will likely continue to follow the standard treatment for that tumor type. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent CUP. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent cancer often experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from cancer is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.