ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use for people with sarcoma. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for sarcoma. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How sarcoma is treated

Sarcoma is rare, and research shows that patients have better outcomes if they are treated at a medical center with experience treating sarcomas. These are called "sarcoma specialty centers."

In cancer care, different types of doctors often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, and others.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the type, stage, and grade of sarcoma, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for sarcomas because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

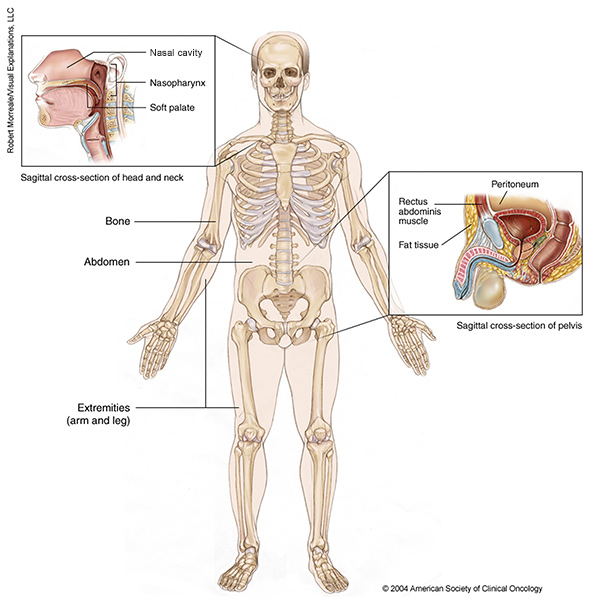

The common types of treatments used for sarcomas are described below. Your care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care. Because there are so many different types of sarcoma, and treatment plans should be individualized, it is not possible to describe the best treatments for each of the rare sarcomas in this section.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. Before surgery, it is important to have a biopsy and appropriate imaging scans to confirm the diagnosis (see Diagnosis). After a biopsy, surgery is typically an important part of the treatment plan if the tumor is localized (located in only 1 area). Surgical oncologists and orthopedic oncologists are doctors who specialize in treating sarcomas using surgery.

The surgeon's goal is to remove the tumor and enough normal tissue surrounding it to obtain a clean margin around the tumor. A “clean margin” means there are no tumor cells visible at the borders of the surgical specimen. This is currently the best method available to ensure that there are no tumor cells left in the area from which the tumor was removed. Small low-grade sarcomas can usually be effectively removed by surgery alone. Those that are high grade and larger than 2 inches (5 cm) are often treated with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. Radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be used before surgery to shrink the tumor and make removal easier. They also may be used during and after surgery to destroy any remaining cancer cells.

Rarely, for patients with a very large tumor involving the major nerves and blood vessels of the arm or leg, surgical removal of the limb is required to control the tumor. This is called amputation. This surgery can also be necessary if the tumor grows back in the arm or leg after surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy have been completed. It’s important to remember that the operation that results in the most useful and strongest limb may be different from the one that gives the most normal appearance. If amputation is needed, rehabilitation, including physical therapy, can help maximize physical function. Rehabilitation can also help a person cope with the social and emotional effects of losing a limb. People who have had an amputation can often wear a prosthesis, which is an artificial body part, depending on the type of amputation.

If the sarcoma is found at an early stage and has not spread from where it started, surgical treatment is often very effective and many people are cured. However, if the sarcoma has spread to other parts of the body, treatment can usually control the tumor but not cure it.

Some sarcomas cannot be removed using surgery. Some sarcomas cannot be reached surgically or may involve critical structures that cannot be removed. For example, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver usually affects many parts of the liver at once and other parts of the body. As a result, surgery, even liver transplantation, cannot completely eliminate the cancer. This is similar to the situation for 80% of people with cardiac sarcoma. By the time the cardiac tumor causes symptoms, it has already spread and cannot be completely removed with surgery. In these situations, radiation therapy or chemotherapy will typically be recommended instead (see below).

Before surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have, including the recovery period. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. Since sarcomas are rare, it is very important to talk with a radiation oncologist who has experience treating sarcomas.

A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

Radiation therapy may be done before surgery to shrink the tumor so that it may be more easily removed. Or it may be done after surgery to remove any cancer cells left behind. Radiation treatment may make it possible to do less surgery, often preserving important structures in the arm or leg if the sarcoma is located in any of those places.

Radiation therapy can damage normal cells, but because it is focused around the tumor, side effects are usually limited to those areas.

External-beam radiation therapy

The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body.

The way external-beam radiation is used has changed over the past 20 years. It is now possible to give many small beams of radiation that turn on and off as the radiation machine rotates around the body. This is called intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and this approach is commonly used for sarcomas. IMRT focuses more radiation on the tumor site and less on the normal tissues. As a result, there are fewer side effects than there were in the past. Similarly, stereotactic body radiation treatment (SBRT) is another type of advanced radiation therapy that is used with image guidance to treat a small tumor (often smaller than 5 cm).

Proton beam radiation therapy

Proton therapy is a type of external-beam radiation treatment that uses protons rather than x-rays. Like x-rays, protons can destroy cancer cells. It is most commonly used in parts of the body close to critical structures, for example, near the spinal cord or at the base of the brain. Learn more about proton therapy. In addition, radiation treatment using heavier charged particles, known as carbon-ion radiation therapy, is being studied in Japan, Germany, and China for the treatment of sarcomas.

Intraoperative radiation therapy

In some hospitals, part of the planned radiation therapy can be given during surgery. This approach can decrease the need to expose healthy tissue to radiation from external-beam radiation or brachytherapy.

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy is the insertion of radiation seeds through thin tubes called catheters directly into the affected area of the body. Brachytherapy usually requires specialized skills and special training. It is only used in certain hospitals and only in special situations to treat sarcoma.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Side effects from radiation therapy depend on what part of the body receives radiation. They may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements.

In the short term, radiation can cause injury to the skin that looks like a sunburn. This is usually treated with creams that keep the skin soft and help relieve discomfort. Radiation therapy can also affect wound healing. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished.

In the long term, radiation can cause scarring that affects the function of an arm or a leg. Radiation therapy can damage the bowels, liver, kidneys, or other internal organs when it is used to treat soft-tissue sarcoma of the retroperitoneum, abdomen, or pelvis.

In rare cases, radiation can cause another sarcoma or other cancer. In the unlikely event that this happens, it can be 7 to 20 years after radiation for a second cancer to develop. Each person is encouraged to talk with their doctor about the possible risks and benefits of the radiation therapy recommended for them. Learn more about radiation therapy.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for sarcomas include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunotherapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is medication that keeps cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells. Cancer cells grow and divide faster than normal cells. However, normal cells also grow and divide, so the side effects of chemotherapy are due to the treatment’s effects on normal cells that are growing and dividing.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time. Chemotherapy for sarcoma can usually be given as an outpatient treatment.

Different drugs are used to treat different types and subtypes of sarcoma. Some types of chemotherapy that might be used alone or in combination for sarcoma include:

-

Doxorubicin (available as a generic drug)

-

Epirubicin (Ellence)

-

Ifosfamide (Ifex)

-

Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

-

Docetaxel (Taxotere)

-

Paclitaxel (available as a generic drug)

-

Trabectedin (Yondelis)

-

Eribulin (Halaven)

-

Dacarbazine (available as a generic drug)

This is a condensed list of some common chemotherapies for sarcoma, since there are over 70 types of soft-tissue sarcoma. There are several other chemotherapies that may be used to treat different types of sarcomas. In some cases, a specific drug or drugs are used only for a particular type of sarcoma.

Chemotherapy is often used when a sarcoma has already spread. It may be given alone or in combination with surgery, radiation therapy, or both.

For example, certain types of sarcomas may be treated with chemotherapy before surgery to make the tumor easier to remove. Chemotherapy given before surgery may be called by different names, including preoperative chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or induction chemotherapy.

If a patient has not received chemotherapy before surgery, chemotherapy may be given to destroy any microscopic tumor cells that remain after a patient has recovered from surgery. Chemotherapy given after surgery is called adjuvant chemotherapy or postoperative chemotherapy.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These side effects usually go away after treatment is finished. In rare cases, there are long-term problems that affect the heart or kidneys or cause second cancers.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival, usually by blocking the action of proteins in cells called kinases. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in your tumor. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective treatment whenever possible. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Targeted therapies for soft-tissue sarcoma include:

Imatinib (Gleevec). Imatinib is a type of targeted therapy called a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, also called a TKI. It is the standard first-line treatment for GIST worldwide. Imatinib is also approved for the treatment of people with advanced-stage dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Two other targeted drugs, sunitinib (Sutent) and regorafenib (Stivarga), are approved for the treatment of GIST when imatinib does not work.

Pazopanib (Votrient). Pazopanib is a type of targeted therapy called a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor. It is approved to treat kidney cancer as well as several types of soft-tissue sarcoma.

Tazemetostat (Tazverik). Tazemetostat is a targeted therapy that targets EZH2. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of people 16 and older with epithelioid sarcoma that cannot be removed with surgery. Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare type of sarcoma that often starts in the fingers, hands, arms, or feet of young adults.

Pexidartinib (Turalio). Pexidartinib is a colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) inhibitor that the FDA has approved to treat certain people with tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCT), sometimes called pigmented villonodular synovitis or giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. These are rare tumors that affect the tendons and joints of younger adults. In a recent clinical trial, of the 61 people who took pexidartinib, the drug worked in 39.3% of them and improved their pain, range of motion, and physical function. Pexidartinib can be used to treat people with significant symptoms from TGCT for whom surgery is not considered a good option. Taking pexidartinib did cause serious or potentially fatal side effects that affected the liver in some patients. Therefore, it can only be prescribed by a certified specialist, and patients must enroll in a patient registry.

Sirolimus protein-bound particles (Fyarro). Sirolimus is a kinase inhibitor that targets the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). This medication may be given as an infusion to treat perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) that is locally advanced and cannot be removed with surgery, as well as metastatic malignant PEComa. PEComa is a type of rare tumor that forms in the soft tissues of the stomach, intestines, lungs, female reproductive organs, and genitourinary organs. Most PEComas are benign. They often occur in children with an inherited condition called tuberous sclerosis.

Tumor-agnostic treatments. A small percentage of sarcomas, less than 1%, have a mutation in the neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene. Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) and entrectinib (Rozlytrek) are NTRK inhibitors that are approved for any cancer that has a specific gene fusion in the NTRK gene.

Clinical trials are taking place to find out more about new treatments for rare sarcomas unique to specific body parts. See the Latest Research section for more information.

Return to top

Immunotherapy (updated 01/2023)

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells.

Immunotherapy is generally not approved for the treatment of sarcomas because they have not yet shown significant benefit in most sarcomas. Many recently approved immunotherapy treatments for other types of cancers involve “immune checkpoint inhibitors.” These drugs are given to take the brakes off the body’s natural immune response against the cancer in the body. The current immunotherapy treatments can cause problems because these drugs also activate immune responses against normal body parts, leading to side effects from an overactive immune system.

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq). Atezolizumab is a type of immune checkpoint inhibitor. It is approved for alveolar soft part sarcoma.

Tumor-agnostic treatments. In a small percentage of sarcomas (less than 1%), testing on a tumor may show that it has high tumor mutational burden or specific problems with repairing DNA damage, called microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). If these problems are present, then a checkpoint inhibitor called pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or dostarlimab (Jemperli) may be used.

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include skin reactions, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight changes. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for the immunotherapy recommended for you. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Organ transplantation

Organ transplantation involves replacing an organ affected by sarcoma with a healthy organ from a donor. Organ transplant is very rarely used to treat sarcomas. However, there are examples of heart transplantation used as a treatment for cardiac sarcoma and liver transplantation used to treat an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma that is only growing in the liver.

For a transplant to be successful, the patient will have to take immunosuppressive medication to help the patient’s body accept the donated organ. As a result of taking this medication, a new cancer may develop or the sarcoma might come back. In addition, people may have to wait a long time for a donor organ to become available. Therefore, patients and their doctors should carefully consider and talk about whether this treatment option is right for them.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative care or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to get rid of the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Treatment by stage of sarcoma

Different treatments may be recommended for each stage of sarcoma. Below are generalized treatment options by stage. For more detailed descriptions, see “How sarcoma is treated,” above. Your doctor will work with you to develop a specific treatment plan for you based on the cancer’s stage and other factors. Clinical trials may also be a treatment option for each stage.

When considering the treatment plan, doctors will often divide sarcomas into 2 categories: curable and treatable. Curable sarcomas can be completely removed from the body, with the goal of preventing it from coming back. Treatable sarcomas cannot be totally removed from the body but can be controlled for some time with treatments. In many cases, stage I to stage III sarcoma is curable and stage IV, or metastatic, sarcoma is treatable.

Stage I sarcoma

At this early stage, sarcoma can often be completely removed with surgery. Treatment with radiation therapy before or after surgery is sometimes recommended.

Stage II sarcoma

Stage II sarcoma is often high grade and can grow and spread quickly. Treatments at this stage include surgery plus radiation therapy. If the tumor is hard to reach, radiation therapy may be used first to shrink the tumor. This is called neoadjuvant treatment. Or, if the tumor can be removed with surgery, radiation therapy may be used afterward to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back. This is called adjuvant treatment. There are risks and benefits to giving radiation therapy before versus after surgery, and the decision to use it must be made based on a person's individual situation.

Stage III sarcoma

Stage III sarcoma is also high grade and larger. Typically treatment will involve a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. Chemotherapy may also be added to the treatment plan. Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both may be given before and/or after surgery to shrink tumors and lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

Metastatic (stage IV) sarcoma

If cancer spreads to another part in the body from where it started, doctors call it metastatic cancer. If this happens, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have experience in treating it. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan. Clinical trials might also be an option. Learn more about getting a second opinion at a sarcoma specialty center before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan.

Your treatment plan may include medications as described above and other palliative treatments to help relieve symptoms and side effects. In addition to providing symptom relief, medical treatments such as chemotherapy may also slow the spread of the cancer. The type of medical treatment that is recommended will depend on many factors, such as the type of sarcoma, which treatments you have received before, and your medical history. Clinical trials involving new drugs or combinations of drugs may also be considered.

Surgery may be used to remove individual metastases, especially if the cancer has spread to a lung, but only a small percentage of people benefit from this. This surgical procedure is called metastatectomy. Radiation therapy can also be used to help relieve symptoms and side effects. If cancer has spread to the liver, localized treatments may be recommended, such as surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Occasionally, when the tumor is not growing, a “watch and wait” approach, also called “active surveillance,” may be used. This means that the patient is closely monitored and active treatment begins only if the tumor begins to grow or cause symptoms.

For many people, a diagnosis of metastatic cancer is very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of your health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (regional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence). If the sarcoma was originally in the arm or leg, the recurrence most commonly occurs in the lungs. Patients treated for sarcoma of the abdomen or torso are at risk for local, regional, or distant recurrence.

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatments described above, such as surgery, therapies using medication, and radiation therapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent sarcoma. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

A local recurrence often can be successfully treated with additional surgery plus radiation therapy, but the risks of side effects from these treatments tends to increase. Treatment for a distant recurrence is most successful when there are a small number of tumors that have spread to the lung that can be completely removed surgically, destroyed with radiofrequency ablation (see below), or destroyed with ablative high-dose radiation therapy (also known as stereotactic body radiotherapy, SBRT, or Gamma Knife radiotherapy):

-

Radiofrequency ablation is a technique where a needle is inserted into the tumor to deliver an electrical current that can destroy the cancer. This burns the tumor from the inside out.

-

SBRT is the use of pinpointed radiation at very high doses over a few treatments to attack a specific small area of tumor. This is a useful technique because it uses fewer treatments and can be more precise than external-beam radiation therapy.

People with recurrent cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from sarcoma is not always possible. If the sarcoma cannot be cured, it can often still be controlled, at least for a period of time. It is important to understand that patients can live with cancer in their body as long as it does not affect the function of a major organ. Therefore, the goal of treatment is to control the cancer and preserve organ function.

If the sarcoma can no longer be controlled, it is called end-stage or terminal cancer. This diagnosis is stressful, and advanced cancer is difficult to discuss for some people. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live fewer than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.