ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use to treat people with oral or oropharyngeal cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for oral and oropharyngeal cancers. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How oral and oropharyngeal cancers are treated

Oral and oropharyngeal cancers can often be cured, especially if the cancer is found at an early stage. Although curing the cancer is the primary goal of treatment, preserving the function of the nearby nerves, organs, and tissues is also very important. When doctors plan treatment, they consider how treatment might affect a person’s quality of life, such as how the person feels, looks, talks, eats, and breathes.

In many cases, a team of doctors will work together with the patient to create the best treatment plan. Head and neck cancer specialists often form a multidisciplinary team to care for each patient. This team may include:

-

Medical oncologist: A doctor who treats cancer using chemotherapy or other medications, such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

-

Radiation oncologist: A doctor who specializes in treating cancer using radiation therapy.

-

Surgical oncologist: A doctor who treats cancer using surgery.

-

Otolaryngologist: A doctor who specializes in the ear, nose, and throat.

-

Reconstructive/plastic surgeon: A doctor who specializes in reconstructive surgery, which is done to help repair damage caused by cancer treatment.

-

Maxillofacial prosthodontist: A specialist who performs restorative surgery in the head and neck areas.

-

Oncologic dentist or oral oncologist: Dentists experienced in caring for people with head and neck cancer.

-

Prosthodontist: A dental specialist with expertise in the restoration and replacement of broken teeth with crowns, bridges, or dentures.

-

Physical therapist: A health care professional who helps patients improve their physical strength and ability to move.

-

Speech-language pathologist: A health care professional who specializes in communication and swallowing disorders. A speech-language pathologist helps patients regain their speaking, swallowing, and oral motor skills after cancer treatment that affects the head, mouth, and neck.

-

Audiologist: A health care professional who treats and manages hearing problems that may be caused by the tumor itself or the cancer treatment.

-

Psychologist/psychiatrist: These mental health professionals address the emotional, psychological, and behavioral needs of the person with cancer and those of their family.

Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, and others. It is extremely important for the team to create a comprehensive treatment plan before treatment begins. People may need to be seen by several specialists before a treatment plan is fully developed.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the type and stage of cancer, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. One of these therapies, or a combination of them, may be used.

Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for oral and oropharyngeal cancers because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

There are 3 main treatment options for oral and oropharyngeal cancer: surgery, radiation therapy, and therapies using medication. These types of treatment are described below. Your care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue, known as a margin, during an operation. An important goal of the surgery is the complete removal of the tumor with "negative margins." Negative margins means that there is no trace of cancer in the margin's healthy tissue. Surgeons are often able to tell in the operating room if all of the tumor has been removed.

Sometimes surgery is followed by radiation therapy, therapies using medication, or both. Depending on the location, stage, grade, and other features of the cancer, some people may need more than 1 operation to remove the cancer and to help restore the appearance and function of the affected tissues.

The most common surgical procedures for the removal of oral or oropharyngeal cancer include:

-

Primary tumor surgery. The tumor and a margin of healthy tissue around it are removed to decrease the chance that any cancerous cells will be left behind. The tumor may be removed through the mouth or through an incision in the neck. A mandibulotomy, in which the jawbone is split to allow the surgeon to reach the tumor, may also be required.

-

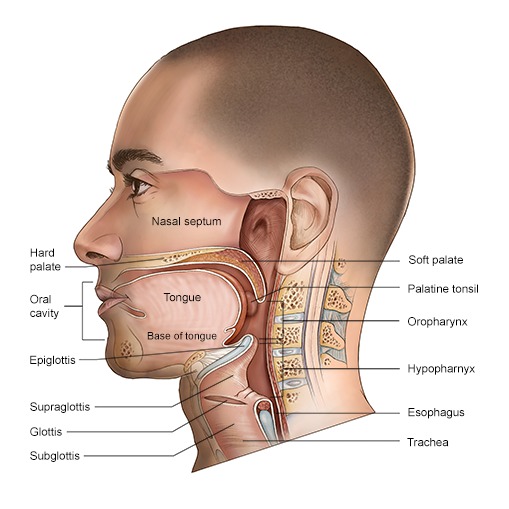

Glossectomy. This is the partial or total removal of the tongue.

-

Mandibulectomy. If the tumor has entered a jawbone but not spread into the bone, then a piece of the jawbone or the whole jawbone will be removed. If there is evidence of destruction of the jawbone on an x-ray, then the entire bone may need to be removed.

-

Maxillectomy. This surgery removes part or all of the hard palate, which is the bony roof of the mouth. Prostheses (an artificial replacement), or more recently, the use of flaps of soft tissue with and without bone can be placed to fill gaps created during this operation.

-

Neck dissection. Cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx often spreads to lymph nodes in the neck. Preventing the cancer from spreading to the lymph nodes is an important goal of treatment. It may be necessary to remove some or all of these lymph nodes using a surgical procedure called a neck dissection, even if the lymph nodes show no evidence of cancer when examined (see Stages and Grades). A neck dissection may be followed by radiation therapy or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, called chemoradiation, to make sure there is no cancer remaining in the lymph nodes. Sometimes, for oropharyngeal cancer, a neck dissection will be recommended after radiation therapy or chemoradiation. If a neck dissection is not possible, radiation therapy may be used instead. See "Radiation therapy," below, for more details on this type of treatment.

-

Laryngectomy. A laryngectomy is the complete or partial removal of the larynx or voice box. Although the larynx is important for producing sounds, the larynx is also critical to swallowing because it protects the airway from food and liquid entering the trachea or windpipe and reaching the lungs, which can cause pneumonia. A laryngectomy is rarely needed to treat oral or oropharyngeal cancer. However, when there is a large tumor of the tongue or oropharynx, the doctor may need to remove the larynx to protect the airway during swallowing. If the larynx is removed, the windpipe is reattached to the skin of the neck where a hole, called a stoma or tracheostomy, is made (see below). Rehabilitation will be needed to learn a new way of speaking (see Follow-up Care).

-

Transoral robotic surgery and transoral laser microsurgery. Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) and transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) are minimally invasive surgical procedures. This means that they do not require large cuts to get to and remove a tumor. In TORS, an endoscope is used to see a tumor in the throat, the base of the tongue, and the tonsils. Then 2 small robotic instruments act as the surgeon’s arms to remove the tumor. In TLM, an endoscope connected to a laser is inserted through the mouth. The laser is then used to remove the tumor. A laser is a narrow beam of high-intensity light.

Other types of surgery may also be needed, including:

-

Micrographic surgery. This type of surgery is frequently used to treat skin cancer and can sometimes be used for oral cavity tumors. It can reduce the amount of healthy tissue removed. This technique is often used with cancer of the lip. It involves removing the visible tumor in addition to small fragments of tissue surrounding the tumor. Each small fragment is examined under a microscope until all of the cancer has been removed.

-

Tracheostomy. If cancer is blocking the airway or is too large to completely remove, a hole is made in the neck. This hole is called a tracheostomy. A tracheostomy tube is then placed, and a person breathes through this tube. A tracheostomy can be temporary or permanent.

-

Gastrostomy tube. If cancer prevents a person from swallowing, a feeding device called a gastrostomy tube is placed. The tube goes through the skin and muscle of the abdomen and directly into the stomach. These tubes may be used as a temporary method for maintaining nutrition until the person can safely and adequately swallow food taken in through the mouth. For swallowing problems that are temporary, a nasogastric (NG) tube may be used instead of a tube into the stomach. An NG tube is inserted through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach.

-

Reconstruction. If treatment requires removing large areas of tissue, reconstructive surgery may be necessary to help the patient swallow and speak again. Healthy bone or tissue may be taken from other parts of the body to fill gaps left by the tumor or replace part of the lip, tongue, palate, or jaw. A prosthodontist may be able to make an artificial dental or facial part to help with swallowing and speech. A speech-language pathologist can teach the patient to communicate using new techniques or special equipment and can also help restore the ability to swallow in patients who have difficulty eating after surgery or after radiation therapy. Learn more about the basics of reconstructive surgery.

In general, surgery for oral and oropharyngeal cancer often causes swelling, making it difficult to breathe. It may cause permanent loss of voice or impaired speech; difficulty chewing, swallowing, or talking; numbness of the ear; weakness raising the arms above the head; lack of movement in the lower lip; and changes to your facial appearance. Surgery can affect the function of the thyroid gland, especially after a total laryngectomy or radiation therapy to the area. Talk with your surgeon about the possible side effects from your specific surgery in advance and how they will be managed or relieved.

It is important that a person receive the opinion of different members of the multidisciplinary team before deciding on a specific treatment. Even though surgery is the fastest way to remove cancer, other treatment methods exist and may be equally effective in treating the cancer. You are encouraged to ask about all of the treatment options before deciding on a treatment plan.

Talk with your health care team before surgery, so you know what to expect and how your side effects will be managed. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

-

External-beam radiation therapy. This is the most common type of radiation treatment for oral or oropharyngeal cancer. During external-beam radiation therapy, a radiation beam produced by a machine outside the body is aimed at the tumor. This is generally done as an outpatient procedure, meaning the patient comes into the center for treatment then returns home after each session.

Proton therapy is a type of external-beam radiation therapy that uses protons rather than x-rays. At high energy, protons can destroy cancer cells. Another method of external-beam radiation therapy, known as intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), allows for more effective doses of radiation therapy to be delivered to the tumor while reducing damage to healthy cells.

-

Internal radiation therapy. When radiation treatment is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy. Tiny pellets or rods containing radioactive materials are surgically implanted in or near the cancer site. The implant is left in place for several days while the person stays in the hospital.

Radiation therapy may be the main treatment for oral cavity cancer, or it can be used after surgery to destroy small areas of cancer that could not be removed. Radiation therapy can also be used to treat the lymph nodes. Combining radiation therapy with cisplatin (a chemotherapy drug; see below) may be used for this purpose in some cases. This approach is called chemoradiation.

Before beginning radiation treatment for any head and neck cancer, people should receive a thorough examination from a dentist with experience treating people with head and neck cancer. Since radiation therapy can cause tooth decay, damaged teeth may need to be removed. Often, tooth decay can be prevented by proper treatment from a dentist before beginning treatment. Learn more about dental and oral health.

It is also important that people receive counseling and evaluation from an oncologic speech-language pathologist. This is a speech-language pathologist who has experience treating people with head and neck cancer. Because radiation therapy can damage healthy tissue, people often have difficulty speaking and/or swallowing after radiation therapy. These problems may occur long after radiation therapy is completed. Speech-language pathologists can provide exercises and techniques to prevent long-term speech and swallowing problems.

Hearing problems may affect patients who receive radiation therapy to the head due to nerve damage or buildup of fluid in the middle ear. Earwax may also dry out and build up because of the radiation therapy’s effect on the ear canal. Sometimes, a patient’s hearing ability may need to be evaluated by a hearing specialist, known as an audiologist.

Radiation therapy may also cause a thyroid problem called hypothyroidism. In this condition, the thyroid gland slows down, causing the patient to feel tired and sluggish. Every patient who receives radiation therapy to the neck area should have their thyroid function checked regularly.

Other side effects from radiation therapy to the head and neck may include redness or skin irritation to the treated area, dry mouth or thickened saliva from damage to salivary glands (which can be temporary or permanent), temporary swelling (called edema) or long-term swelling (called lymphedema), bone pain, nausea, fatigue, mouth sores, sore throat, difficulty opening the mouth, and a loss of appetite due to a change in a person’s sense of taste. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects that you can expect and ways to manage them.

Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications used to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication. Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for oral and oropharyngeal cancer include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Immunotherapy

-

Targeted therapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

Some people may receive chemotherapy in their doctor's office or an outpatient clinic. Others may go to the hospital.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time.

The use of chemotherapy in combination with radiation therapy, called chemoradiation, is often recommended. The combination of these 2 treatments can sometimes control tumor growth, and it often is more effective than giving either of these treatments alone. This combined treatment, using cisplatin, may be an option for oral or oropharyngeal cancer that may have spread to the lymph nodes. Sometimes, chemoradiation for oropharyngeal cancer will be followed with neck dissection (see "Surgery," above). However, the side effects can be worse when combining these treatments.

Chemotherapy may be used as the initial treatment before surgery, radiation therapy, or both, which is called a neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Or it can be given after surgery, radiation therapy, or both, which is called adjuvant chemotherapy. Chemotherapy for oral cavity cancer is most often given as part of a clinical trial.

Each drug or combination of drugs can cause specific side effects. While some can be permanent, most are temporary and can typically be well controlled. In general, chemotherapy may cause fatigue, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, dry mouth, hearing loss, loss of appetite (often due to a change in sense of taste), difficulty eating food, weakened immune system, diarrhea, constipation, and open sores in the mouth that can lead to infection. Your health care team will help you understand what to expect with your prescriptions and how side effects can be managed.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system's ability to attack cancer cells.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) are 2 immunotherapy drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of people with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) that has not been stopped by platinum-based chemotherapy (see below for information on recurrent cancer and metastatic cancer). Both are immune checkpoint inhibitors that are also approved for the treatment of some people with advanced cancers of other kinds.

Immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy and radiation therapy may also be used in clinical trials.

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include skin reactions, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight changes. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for the immunotherapy recommended for you. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in your tumor. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective treatment whenever possible. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them.

Currently, antibodies directed against a cellular receptor called the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are being used in combination with radiation therapy for head and neck cancers. Cetuximab (Erbitux) is a targeted therapy approved by the FDA for this use in combination with radiation therapy.

Talk with your doctor about the possible side effects of the specific treatment you will be receiving and how they can be managed.

Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative care or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to get rid of the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Metastatic cancer

If cancer spreads to another part in the body from where it started, doctors call it metastatic cancer. If this happens, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have experience in treating it. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan. Clinical trials might also be an option. Learn more about getting a second opinion before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan.

Your treatment plan may include a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy. Palliative care will also be important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

For most people, a diagnosis of metastatic oral or oropharyngeal cancer is very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of your health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (regional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence).

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatments described above, such as surgery, medications, and radiation therapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from cancer is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your doctor and health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.