ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use for children and young adults with Ewing sarcoma. Use the menu to see other pages.

In general, cancer in children and young adults is uncommon. This means it can be hard for doctors to plan treatments unless they know what has been most effective in this age group. That is why more than 60% of children and teens with cancer are treated as part of a clinical trial. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. The “standard of care” is the best treatments known based on previous clinical trials. Clinical trials may test approaches such as a new drug, a new combination of existing treatments, or new doses of current therapies. The health and safety of all people participating in clinical trials are closely monitored.

To take advantage of these newer treatments, children and teens with Ewing sarcoma should be treated at a specialized cancer center. Doctors at these centers have extensive experience in treating this age group and have access to the latest research. A doctor who specializes in treating children and teens with cancer is called a pediatric oncologist. If a pediatric cancer center is not nearby, general cancer centers sometimes have pediatric specialists who are able to be part of your child’s care.

How Ewing sarcoma is treated

In many cases, a team of doctors works with a child and the family to provide care. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Pediatric cancer centers often have extra support services for children and teens and their families, such as child life specialists, dietitians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, and counselors. Special activities and programs to help your family cope may also be available. Learn more about the clinicians who provide cancer care.

It is important that patients are seen by medical experts from different specialties across medical disciplines who are experienced with treatment of Ewing sarcoma from the time of diagnosis. This includes a:

-

Radiologist. A doctor trained in diagnosing and treating cancer using medical imaging.

-

Medical oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with systemic treatments using medications.

-

Pediatric oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer in children and teens.

-

Pathologist. A doctor who diagnoses disease by explaining laboratory tests and evaluating cells, tissues, and organs.

-

Surgical or orthopedic oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer using surgery.

-

Radiation oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with radiation therapy. This doctor will be part of the team if radiation therapy is recommended.

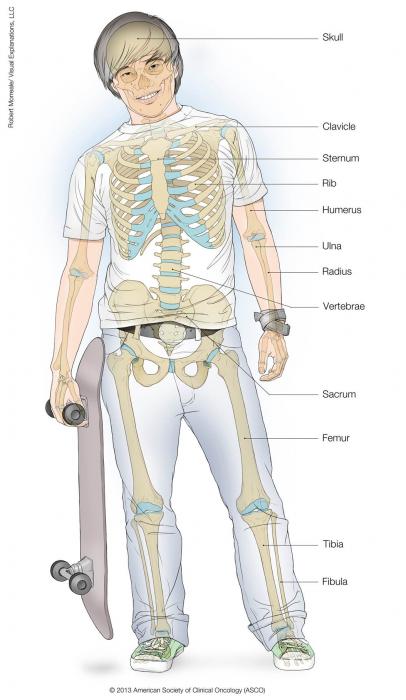

It is extremely important that the biopsy incision (see Diagnosis) is placed in the best location. Therefore, the surgical or orthopedic oncologist who will perform the surgery should be involved in the decision regarding where the biopsy incision will be made. This is particularly important if the tumor can be totally removed or, if the tumor is located in an arm or leg, whether a limb-sparing procedure can be done.

Children and young adults with Ewing sarcoma should be treated in clinical trials specifically designed for their disease. A typical treatment plan for Ewing sarcoma includes systemic therapy with medication that treats the entire body, such as chemotherapy, combined with localized therapy. Systemic therapy is the use of medication to destroy cancer cells. Localized therapy focuses on treating the tumor itself using surgery, radiation therapy, or both. When more than 1 treatment is used, it is called combination therapy.

Doctors make treatment recommendations based on the stage of the disease and the age of the patient, while trying to avoid or reduce long-term side effects of treatment.

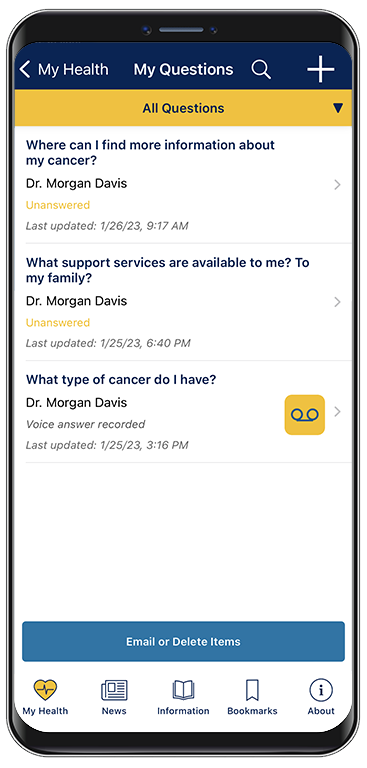

Take time to learn about all of the treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with the doctor about the goals of each treatment and what your child can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of conversations are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your child's doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your child’s care. Shared decision-making is important for Ewing sarcoma because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

The common types of treatment used for Ewing sarcoma are described below. The care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care. Learn more about preparing your child for treatment.

READ MORE BELOW:

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells. Chemotherapy is given by a pediatric or medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication. Some patients may receive chemotherapy in their doctor’s office, while others may go to a hospital or outpatient clinic.

Systemic chemotherapy gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Common ways to give systemic chemotherapy include an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). However, chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma is usually injected into a vein or muscle; it is rarely given by mouth.

When possible, treatment for Ewing sarcoma begins with chemotherapy. After this first chemotherapy is finished, the doctor may use localized surgery or radiation therapy (see below) followed by more chemotherapy to get rid of any remaining cancer cells. When chemotherapy is used before another treatment, it is called “neoadjuvant chemotherapy.” Other times, the doctor may use surgery or radiation therapy first and then give chemotherapy after. This is called “adjuvant chemotherapy.”

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or combinations of different drugs given at the same time. Children and young adults with Ewing sarcoma should receive cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), etoposide (Toposar, VePesid), ifosfamide (Ifex), and/or vincristine (Oncovin, Vincasar PFS). For Ewing sarcoma that has not spread to other parts of the body, the standard schedule is chemotherapy every 2 weeks. Patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma may also be treated with the above medications and dactinomycin (Cosmegen).

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These side effects usually go away after treatment is finished.

Children and young adults receiving chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma may be at risk for developing neutropenia, which is an abnormally low level of a type of white blood cell called neutrophils. All white blood cells help the body fight infection. The doctor may give the patient medications to increase their white blood cell levels. These medications are called white blood cell growth factors, also known as colony-stimulating factors (CSFs). Treating neutropenia is an important part of the overall treatment plan.

In addition, parents of children and young adults receiving chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma should talk with the doctor about fertility preservation, including sperm storage, before chemotherapy starts.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. An orthopedic oncologist is usually the doctor who will perform the surgery.

When possible, surgical removal of the tumor should happen after chemotherapy. Surgery may also be needed to remove any remaining cancer cells after chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Often, a tumor can be removed without causing disability. However, if the tumor occurs in an arm or leg, surgery to remove much of the bone may affect the limb’s ability to function. Bone grafts from other parts of the body may help reconstruct the limb, and a prosthesis made of metal or plastic bones or joints can replace lost tissue. Physical therapy after surgery can help children and young adults learn to use the limb again. Support services are available to help patients cope with the emotional effects of the loss of a limb. Learn more about rehabilitation services.

Before surgery, talk with the health care team about possible side effects from the specific surgery your child will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other high-energy particles to destroy tumor cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. For Ewing sarcoma, radiation therapy is used when surgery is not possible or if surgery did not remove all of the tumor cells, as well as when chemotherapy was not effective.

The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body. When radiation therapy is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time. Intraoperative radiation therapy, which is given inside the body during surgery, is being studied in clinical trials.

Side effects from radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished. In the long term, radiation therapy can also interfere with normal bone growth and increase the risk of developing a secondary cancer. Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Bone marrow transplant/stem cell transplant

For Ewing sarcoma, a bone marrow transplant is an approach that is still being studied to find out if it is an effective treatment option. It should only be done as part of a clinical trial.

A bone marrow transplant is a medical procedure in which bone marrow that contains cancer is replaced by highly specialized cells. These cells, called hematopoietic stem cells, develop into healthy bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells are blood-forming cells found both in the bloodstream and in the bone marrow. This procedure is also called a stem cell transplant or hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Before recommending a transplant, doctors will talk with the patient and family about the risks of this treatment. They will also consider several other factors, such as the type of tumor, results of any previous treatment, and the child’s age and general health.

There are 2 types of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, depending on the source of the replacement blood stem cells: allogeneic (ALLO) and autologous (AUTO). ALLO uses donated stem cells, while AUTO uses the person’s own stem cells. AUTO transplants are the type used most commonly to treat Ewing sarcoma.

The goal of stem cell transplantation is to destroy all of the cancer cells in the marrow, blood, and other parts of the body using high doses of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and then allow replacement blood stem cells to create healthy bone marrow.

Side effects depend on the type of transplant, the person's general health, and other factors. Learn more about the basics of bone marrow and stem cell transplantation.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, social, and financial effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative and supportive care. It is an important part of your child’s care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative and supportive care focuses on improving how your child feels during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative and supportive care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. Your child may also receive palliative treatments, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy, to improve symptoms.

Before treatment begins, talk with your child’s doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative and supportive care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

Cancer care is often expensive, and navigating health insurance can be difficult. Ask your doctor or another member of your health care team about talking with a financial navigator or counselor who may be able to help with your financial concerns.

During treatment, your child’s health care team may ask you to answer questions about your child’s symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if your child is experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative and supportive care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with the doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding the risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help everyone feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent disease. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (regional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence). When it occurs, recurrence is most common within the first 2 years after Ewing sarcoma treatment has finished. However, it is also important to note that late recurrences that develop up to 5 years after treatment are more common with Ewing sarcoma than with other types of cancers in this age group.

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, the doctor will talk about the treatment options with you. The next round of treatment will depend on where and when the cancer recurred and how it was first treated. The doctor may recommend chemotherapy, including cyclophosphamide (available as a generic drug) and irinotecan (Camptosar), temozolomide (Temodar), and topotecan (Hycamtin, Brakiva); radiation therapy; and/or surgery to remove new tumors. Bone marrow/stem cell transplantation may also be recommended.

The doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent Ewing sarcoma. Or, they may suggest having the tumor analyzed for changes in genes that can be targeted by specific drugs. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative and supportive care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent Ewing sarcoma and their family sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your child's health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help your family cope. Learn more about dealing with a recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Although treatment is successful for many children and young adults with cancer, sometimes it is not. If the Ewing sarcoma cannot be cured or controlled, this is called advanced or terminal disease.

This diagnosis is stressful, and advanced cancer may be difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with the health care team to express your family’s feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help.

Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are expected to live less than 6 months. Parents and guardians are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Some children and young adults may be happier and more comfortable if they can attend school part-time or keep up other activities and social connections. The health care team can help parents or guardians decide on an appropriate level of activity. Making sure the patient is physically comfortable and free from pain is extremely important as part of end-of-life care. Learn more about caring for a terminally ill child and advanced cancer care planning.

The death of a child is an enormous tragedy, and families may need support to help them cope with the loss. Pediatric cancer centers often have professional staff and support groups to help with the process of grieving. Learn more on grieving the loss of a child.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for children and young adults with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.