ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different treatments doctors use for people with ALL. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section tells you the treatments that are the standard of care for this type of leukemia. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, patients are encouraged to consider clinical trials as an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors want to learn whether the new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. To learn more about clinical trials, see the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections.

Treatment overview

In cancer care, different types of doctors often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, and others.

Descriptions of the most common treatment options for ALL are listed below. Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the subtype and classification of ALL, possible side effects, the patient’s preferences and overall health. Your care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by ending the cancer cells’ ability to grow and divide.

Chemotherapy is given by a medical oncologist or a hematologist. A medical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication. A hematologist is a doctor who specializes in treating blood disorders.

Systemic chemotherapy gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Common ways to give chemotherapy include:

-

An intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle. It may be given into a larger vein or a smaller vein, such as in the arm. When it is given into a larger vein, a central venous catheter or port may need to be placed in the body.

-

An injection given into a muscle

-

In a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally)

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. Patients with ALL receive several different drugs throughout their treatment.

A patient may receive chemotherapy during different stages of treatment:

- Remission induction therapy. This is the first round of treatment given during the first 3 to 4 weeks after diagnosis. It is designed to destroy most of the leukemia cells, stop symptoms of the disease, and return the blood counts to normal levels.

The specific treatments used may include:

-

Daunorubicin (Cerubidine)

-

Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cyclophosphamide (Neosar), or vincristine (Vincasar), given by an injection into a vein

-

Asparaginase (Elspar) or Pegasparaginase (Oncaspar), given by injection into a muscle, under the skin or into a vein

-

Dexamethasone (multiple brand names) or prednisone (multiple brand names) by mouth

-

Methotrexate (multiple brand names) or cytarabine (Cytosar-U) as an injection into the spinal fluid

-

Treatments that targeted the Philadelphia chromosome (see Targeted therapy, below)

The goal of induction therapy is a complete remission (CR). This means that the blood counts have returned to normal, the leukemia cannot be seen when a bone marrow sample is examined under the microscope, and the signs and symptoms of the ALL are gone. More than 95% of children and 75% to 80% of adults with ALL will have a CR.

However, small amounts of leukemia can remain after treatment even if it cannot be seen with a microscope. For this reason, it is necessary to give additional therapy to prevent the ALL from coming back. Techniques can be used to find small amounts of leukemia, called minimal residual disease (MRD). These are used to help predict a patient’s prognosis and guide treatment options.

-

Remission consolidation or intensification therapy. This stage of therapy involves the use of a combination of drugs. The drugs may be different or have different doses than those used to achieve remission. Some drugs may be the same as what was given during remission induction therapy. Depending on the subtype of the ALL, the doctor may recommend several courses of consolidation therapy.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy cells.

Recent studies show that not all cancers have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors involved in your leukemia. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective treatment whenever possible. In addition, many research studies are taking place now to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

For ALL, targeted therapy is recommended in addition to standard chemotherapy for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL (Ph+ ALL). Such drugs include:

-

Imatinib (Gleevec)

-

Dasatinib (Sprycel)

-

Nilotinib (Tasigna)

Other targeted therapy drugs used for ALL include:

-

Ponatinib (Iculsig) for Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL

-

Nelarabine (Arranon), a new drug that targets T-cell ALL

-

Rituximab (Rituxan), used in addition to chemotherapy for the treatment of B-cell ALL

-

Blinatumumab (Blincyto)

-

Inotuzumab ozogamicin

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for a specific medication and how they can be managed.

Side effects of chemotherapy and targeted therapy

Induction therapy usually begins in the hospital. Patients will often need to stay in the hospital for 3 to 4 weeks during treatment. However, depending on the situation, many patients can leave the hospital. Those who do, usually need to visit the doctor regularly during treatment.

Some patients will need to stay in the hospital for consolidation therapy but most are able to go home. Many patients with ALL can return to school or work while receiving maintenance therapy.

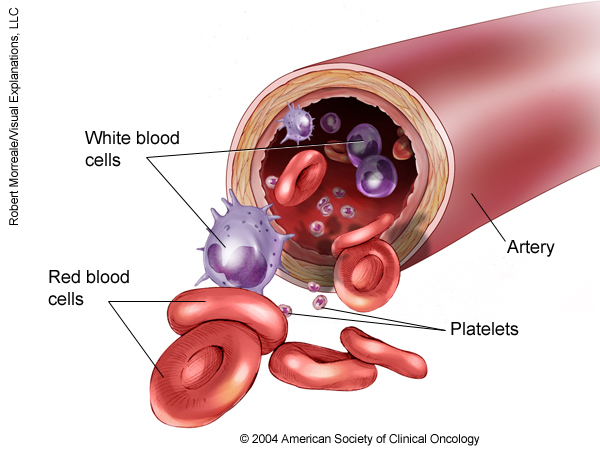

Chemotherapy attacks rapidly dividing cells, including those in healthy tissue such as the hair, lining of the mouth, intestines, and bone marrow. This means that patients receiving chemotherapy may lose their hair, develop mouth sores, or have nausea and vomiting.

Because of changes in the blood counts, most patients will need transfusions of red blood cells and platelets at some point during their treatment. Treatment with antibiotics to prevent or treat infection is usually needed as well. Chemotherapy may lower the body’s resistance to infection by reducing the number of neutrophils. It can also cause bruising and bleeding because of the decrease in the number of platelets and other problems with blood clotting. Chemotherapy may cause fatigue by lowering the number of red blood cells.

Chemotherapy may affect fertility, which is the ability to have a child in the future, and it increases the risk of developing a second cancer. Patients may want to talk with a fertility specialist before treatment begins, as there are options available to help preserve fertility. Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy and preparing for treatment.

The side effects of targeted therapy include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, edema or swelling in the legs or around the eyes, and, rarely, fluid in the lungs. The side effects of targeted therapies for ALL are usually not severe and can be managed.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time. For ALL, radiation therapy to the brain is sometimes used to destroy cancerous cells around the brain and spinal column.

Side effects from radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished. Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

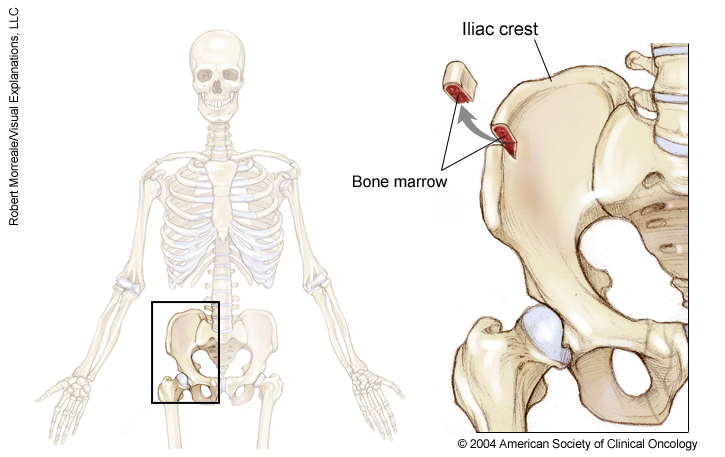

Stem cell transplantation/bone marrow transplantation

A stem cell transplant is a medical procedure in which bone marrow that contains leukemia is destroyed and then replaced by highly specialized cells, called hematopoietic stem cells, that develop into healthy bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells are blood-forming cells found both in the bloodstream and in the bone marrow. These stem cells make all of the healthy cells in the blood. Today, this procedure is more commonly called a stem cell transplant, rather than bone marrow transplant, because it is the stem cells in the blood that are typically being transplanted, not the actual bone marrow tissue.

Before recommending transplantation, doctors will talk with the patient about the risks of this treatment and consider several other factors, such as the type of cancer, results of any previous treatment, and patient’s age and general health.

There are 2 types of stem cell transplantation depending on the source of the replacement blood stem cells: allogeneic (ALLO) and autologous (AUTO). ALLO uses donated stem cells, while AUTO uses the patient’s own stem cells. However, AUTO transplants are generally not used to treat ALL. In both types, the goal is to destroy all of the cancer cells in the marrow, blood, and other parts of the body using high doses of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy and then allow replacement blood stem cells to create healthy bone marrow.

Side effects depend on the type of transplant, your general health, and other factors. Learn more about the basics of stem cell and bone marrow transplantation.

Getting care for symptoms and side effects

ALL and its treatment often cause side effects. In addition to treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the disease, an important part of care is relieving a person’s symptoms and the side effects of treatment. This approach is called palliative or supportive care, and it includes supporting the patient with his or her physical, emotional, and social needs.

Palliative care is any treatment that focuses on reducing symptoms, improving quality of life, and supporting patients and their families. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive palliative care. It works best when palliative care is started as early as needed in the cancer treatment process. People often receive treatment for the leukemia at the same time that they receive treatment to ease side effects. In fact, patients who receive both at the same time often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to eliminate the leukemia, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the treatment plan.

Before treatment begins, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects of your specific treatment plan and palliative care options. During and after treatment, be sure to tell your doctor or another health care team member if you are experiencing a problem so it can be addressed as quickly as possible. Learn more about palliative care.

Refractory ALL

Refractory ALL occurs when a complete remission is not achieved because the drugs did not destroy enough leukemia cells. These patients often continue to have low blood counts, need transfusions, and have a risk of bleeding or infection.

If you are diagnosed with refractory leukemia, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have experience in treating it. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan. Also, clinical trials might be an option. Learn more about getting a second opinion before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan chosen.

Your treatment plan may include new drugs being tested in clinical trials or ALLO stem cell transplantation. Palliative care will also be important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

For most patients, a diagnosis of refractory leukemia is very stressful and, at times, difficult to bear. Patients and their families are encouraged to talk about the way they are feeling with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of the health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, including through a support group.

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when ALL cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it’s important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the leukemia returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the disease does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the leukemia does return after the original treatment, it is called recurrent or relapsed leukemia. When this occurs, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about the recurrence. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about your treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatments described above, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and radiation therapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent ALL. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

Treatment for recurrent ALL depends on the length of the remission and is usually given in cycles for 2 to 3 years. If a recurrence occurs after a long remission, the leukemia may respond again to the original treatment. If the remission was short, then other drugs are used. These are often new drugs being tested in clinical trials.

An ALLO stem cell transplant is generally recommended for patients whose leukemia has come back after a second remission. The drug clofarabine (Clolar) may be used for patients between ages 1 and 21 who have recurrent or refractory ALL after already receiving at least 2 types of chemotherapy. Liposomal vincristine (Marqibo) may also be an option. Supportive care will also be important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent leukemia often experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. Patients are encouraged to talk with their health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help them cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

If treatment doesn’t work

Recovery from leukemia is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

This diagnosis is stressful because the disease is not curable, and for many people, advanced ALL is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your doctor and health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team is there to help, and many team members have special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families. Making sure a person is physically comfortable and free from pain is extremely important.

Patients who have advanced leukemia and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider a type of palliative care called hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. You may use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.