ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use to treat people with multiple myeloma. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for multiple myeloma. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. Information in this section is based on medical standards of care for multiple myeloma in the United States. Treatment options can vary from one place to another.

When making treatment plan decisions, you are also encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials offer additional options to consider. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Research for new myeloma treatments is very active, and many clinical trials are offered. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How multiple myeloma is treated

In cancer care, different types of doctors who specialize in cancer, called oncologists, often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include other health care professionals, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, oncology social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and others. Learn more about the clinicians who provide cancer care.

The treatment of multiple myeloma depends on whether the patient is experiencing symptoms (see Stages) and the patient’s overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan. The goals of treatment are to eliminate myeloma cells, control tumor growth, control pain, and allow patients to have an active life. While there is no cure for multiple myeloma, the cancer can be managed successfully in many patients for years.

Take time to learn about all of your treatment options, including clinical trials, and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Also, talk about the goals of each treatment with your doctor and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of conversations are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is important for multiple myeloma because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

The common types of treatments used for multiple myeloma are described below. Your care plan may also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care. The information below explains the treatment options for people without symptoms and for people with symptoms. In addition, treatment options may depend on whether the patient is newly diagnosed with myeloma or is experiencing a recurrence of the disease.

READ MORE BELOW:

Treatment overview for people with smoldering multiple myeloma

People with early-stage myeloma and no symptoms, called smoldering multiple myeloma or SMM (see Stages), may simply be closely monitored by the doctor through checkups. This approach is called active surveillance or watchful waiting. As noted previously, if there is evidence of bone thinning, or osteoporosis, periodic infusions of bisphosphonates to reverse this process may be recommended. There are also clinical protocols, or processes, used to evaluate whether using medications called targeted therapy (see below) or immunotherapy (see below and Latest Research) can prevent or delay myeloma from developing into a disease that requires treatment.

If symptoms appear, then active treatment starts. Two clinical trials in high-risk SMM have shown that early treatment can slow the progression to myeloma with symptoms for some patients, but whether this helps people live longer is not known.

Return to top

Treatment overview for patients with symptoms

Treatment for people with symptomatic myeloma includes both treatment to control the disease as well as supportive care to improve quality of life, such as by relieving symptoms and maintaining good nutrition. Disease-directed treatment typically includes therapy using medications, such as targeted therapy and/or chemotherapy, with or without steroids. Bone marrow/stem cell transplantation may be an option. Other types of treatments, such as radiation therapy and surgery, are used in specific circumstances.

The treatment plan includes different phases.

-

Induction therapy for rapid control of cancer and to help relieve symptoms.

-

Consolidation with more chemotherapy or a bone marrow/stem cell transplant.

-

Maintenance therapy over a prolonged period to prevent cancer recurrence.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications to take at home, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for multiple myeloma include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunomodulatory drugs

-

Steroids

-

Bone-modifying drugs

-

Immunotherapy

Each of these types of therapies are discussed below in more detail. A person usually receives a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Combination regimens are an important part of the treatment of multiple myeloma. Combining different treatment effects from different types of drugs—such as a combination of an immunomodulatory drug, a proteasome inhibitor, and a steroid—can be an effective way of managing the disease. In addition, other targeted treatments may be added, depending on the individual's specific situation.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient usually receives combinations of different drugs at the same time.

Conventional chemotherapy has been used successfully for the treatment of myeloma. These drugs include cyclophosphamide (available as a generic drug), doxorubicin (available as a generic drug), melphalan (Evomela), etoposide (available as a generic drug), cisplatin (available as a generic drug), carmustine (BiCNU), and bendamustine (Bendeka). Chemotherapy drugs like these may be used in certain situations. For people newly diagnosed with myeloma, these treatments are used less commonly. For example, melphalan is most commonly used when a bone marrow transplantation (see below) is part of the treatment plan. A high dose of melphalan is used to suppress the myeloma for a long time, and the patient's own bone marrow cells are used to recover from this treatment.

It may also be recommended to combine chemotherapy with other types of treatment, including targeted therapies or steroids (see both, below). For instance, the combination of melphalan, the steroid prednisone (multiple brand names), and a targeted therapy called bortezomib (Velcade) is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the initial treatment of multiple myeloma. However, there are several more effective regimens described below that are used much more commonly.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea or constipation. Other side effects include peripheral neuropathy (tingling or numbness in feet or hands), blood clotting problems, and low blood counts. These side effects usually go away once treatment is finished. Occasionally an allergic reaction such as skin rash may occur, and the drug may have to be stopped.

The length of chemotherapy treatment varies from patient to patient and is usually given until the myeloma is well controlled.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells. In recent years, targeted treatment, sometimes called novel therapy, has proven to be increasingly successful at controlling myeloma and improving prognosis. Researchers continue to investigate new and evolving drugs for this disease in clinical trials.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests on cancer cells to identify genes, proteins, and other factors. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective treatment whenever possible. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Targeted therapy for multiple myeloma includes:

-

Proteasome inhibitors. Bortezomib (Velcade), carfilzomib (Kyprolis), and ixazomib (Ninlaro) are classified as proteasome inhibitors. They target specific enzymes called proteasomes that digest proteins in the cells. Because myeloma cells produce a lot of proteins (see the Introduction), they are particularly vulnerable to this type of drug. These drugs may be used to treat newly diagnosed myeloma and recurrent myeloma.

-

Monoclonal antibodies. Elotuzumab (Empliciti) and daratumumab (Darzalex) are monoclonal antibodies that bind to myeloma cells and label them for removal by the person's own immune system. Daratumumab may be given to treat newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. A drug combination of daratumumab and hyaluronidase-fihj (Darzalex Faspro) with or without pomalidomide (Pomalyst) and dexamethasone (multiple brand names) may also be used to treat multiple myeloma. This combination is given under the skin of the abdomen and is quicker than when it is given by injection through a vein. Daratumumab with or without hyaluronidase-fihj combined with carfilzomib and dexamethasone may be used to treat multiple myeloma that has stopped responding to 1 to 3 previous treatments. Isatuximab-irfc (Sarclisa) is a monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with multiple myeloma who have received 1 to 3 previous treatments. Isatuximab-irfc may be given in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone or carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

-

Nuclear export inhibitors. Selinexor (Xpovio) is a targeted therapy that is given in combination with dexamethasone. This combination is used to treat adults with multiple myeloma that has come back after 4 or more previous treatments. It may also be given in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone to people who have received at least 1 previous treatment.

-

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) targeting agent. Belantamab mafodotin-blmf (Blenrep) is an antibody-drug conjugate approved by the FDA to treat adults with recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least 4 previous treatments. Belantamab mafodotin-blmf uses an antibody to bind to BCMA and delivers chemotherapy directly to the myeloma cell. BCMA is a protein on the surface of myeloma cells.

-

Bispecific T-cell engagers (updated 08/2023). Bispecific antibodies can attach to both a T cell and a myeloma cell at the same time, activating an immune attack on the cancer cells. Unlike CAR T cells, bispecific T-cell engagers can be delivered without removing a patient’s immune cells. Elranatamab (Elrexfio), talquetamab (Talvey), and teclistamab-cqyv (Tecvayli) are bispecific T-cell engagers that are approved for the treatment of recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma after at least 4 previous lines of treatment. Elranatamab and teclistamab target the BCMA protein, while talquetamab targets GPRC5D.

Targeted therapies may also be used in combination with chemotherapy (see above), immunomodulatory drugs, or steroid medications (see below), because certain combinations of drugs can sometimes have a better effect than a single drug. For example, the drugs lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, as well as bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone, are offered in combination as initial treatment. Clinical trials are exploring whether the combination of lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone may be as effective as lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone followed by a bone marrow/stem cell transplant (see below).

Lenalidomide and bortezomib can also be effectively used as maintenance therapy to extend the disease's response to the initial therapy or after a bone marrow/stem cell transplant. However, the decision to undergo a transplant is complex and should be discussed carefully with your doctor.

Research has shown that maintenance therapy with lenalidomide and/or bortezomib increases how long patients survive and extends how long they live without active myeloma. Maintenance therapy has to be used with some caution, although recent studies have shown significant improvement with survival using this approach.

Return to top

Immunomodulatory drugs

Lenalidomide (Revlimid) and pomalidomide (Pomalyst) are classified as immunomodulatory drugs, which stimulate the immune system. These drugs also keep new blood vessels from forming and feeding myeloma cells. Thalidomide and lenalidomide are approved to treat newly diagnosed patients. Lenalidomide and pomalidomide are also effective for treating recurrent myeloma.

Return to top

Steroids

Steroids, such as prednisone and dexamethasone, may be given alone or at the same time as other medications, such as targeted therapy or chemotherapy (see above). Steroids are very effective at reducing the burden of plasma cells, but this effect is only temporary.

For example, lenalidomide and dexamethasone as induction and maintenance therapy is recommended for those who are not able to have bone marrow/stem cell transplantation. Adding bortezomib to this combination has recently been shown to be effective in a clinical trial.

Return to top

Bone-modifying drugs

Most people with myeloma receive treatment with bone-modifying drugs. These drugs help strengthen the bone and reduce bone pain and the risk of fractures.

There are 2 types of bone-modifying drugs available for treating bone loss from multiple myeloma. The choice of medications depends on your overall health and your individual risk of side effects.

-

Bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid (Zometa) and pamidronate (Aredia), block the cells that dissolve bone, called osteoclasts. For multiple myeloma, either pamidronate or zoledronic acid is given by IV every 3 to 4 weeks. Each treatment of pamidronate lasts at least 2 hours, and each treatment of zoledronic acid lasts at least 15 minutes. Patients with existing severe kidney problems usually receive lower doses of pamidronate given over a longer time (such as 4 to 6 hours instead of 2 hours). Zoledronic acid is generally not recommended for people with severe kidney problems.

-

Denosumab (Xgeva) is an osteoclast-targeted therapy called a RANK ligand inhibitor. It is approved to treat multiple myeloma and may be an option for people with severe kidney problems. Denosumab has been shown to have similar effectiveness to bisphosphonates.

Treatment with a bone-modifying drug is recommended for up to 2 years. At 2 years, treatment may be stopped if it is working. If the myeloma comes back and new bone problems develop, treatment with a bone-modifying drug is usually started again. Talk with your doctor for more information about stopping and restarting treatment with these medications.

Side effects of bisphosphonates may include flu-like symptoms, anemia, joint and muscle pain, and kidney problems. If you are taking pamidronate or zoledronic acid, you should have a blood test to check how well the kidneys are working before each time you receive the drug. Side effects of denosumab may include diarrhea, nausea, anemia, and back pain.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is an uncommon but potentially serious side effect of both types of bone-modifying drugs. The symptoms may include pain, swelling, and infection of the jaw; loose teeth; and exposed bone. Before treatment, patients should receive a thorough dental examination, and any tooth or mouth infections should be treated. While receiving treatment with a bone-modifying drug, patients should avoid having any invasive dental work done, such as dental surgery. Take care of your teeth, gums, and tongue with regular brushing and flossing. Learn more about dental and oral health during cancer treatment.

Bone-modifying drugs are not always recommended for people with the following conditions:

-

Solitary plasmacytoma (1 bone tumor)

-

Smoldering or indolent myeloma

-

Conditions of abnormal plasma cells that are not myeloma but may eventually become myeloma, such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)

This information on bone-modifying drugs is based on ASCO recommendations for bisphosphonate treatment for multiple myeloma. (Please note that this link takes you to a different ASCO website.)

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells.

The cellular immunotherapies approved to treat multiple myeloma are idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Carvykti). These are chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies that target BCMA. BCMA is a protein on the surface of myeloma cells. These treatments may be used to treat multiple myeloma that has not been stopped by 4 or more treatments.

In CAR T-cell therapy, some T cells are removed from a patient’s blood. Then, the cells are changed so they have specific proteins called receptors. The receptors allow the changed T cells to recognize the cancer cells. In the case of idecabtagene vicleucel and ciltacabtagene autoleucel, the cells recognize the BCMA protein. The changed T cells are then returned to the patient’s body. Once there, they seek out and destroy cancer cells. Learn more about the basics of CAR T-cell therapy.

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include skin reactions, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight changes. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for the immunotherapy recommended for you. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

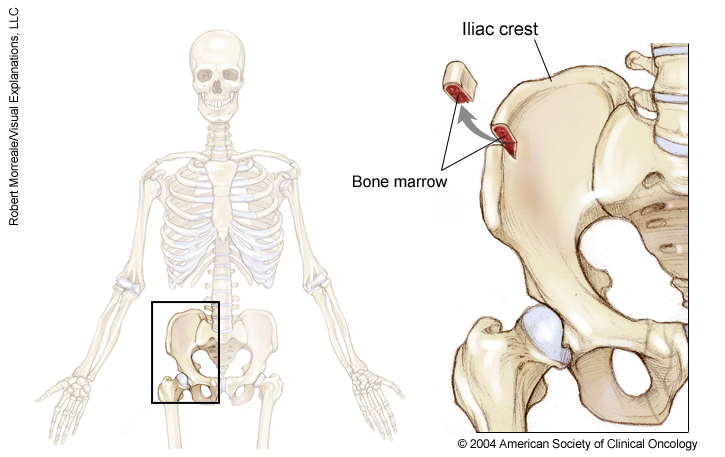

Bone marrow transplant/stem cell transplant

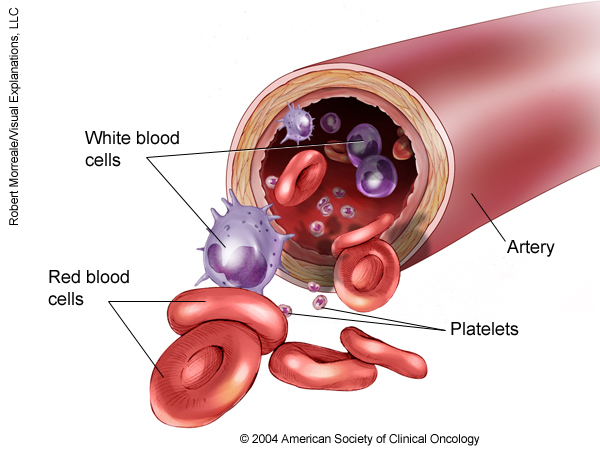

A bone marrow transplant is a medical procedure in which bone marrow that contains cancer is replaced by highly specialized cells. These cells, called hematopoietic stem cells, develop into healthy red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in the bone marrow. Hematopoietic stem cells are blood-forming cells found both in the bloodstream and in the bone marrow. This procedure is also called a stem cell transplant.

Before recommending a transplant, doctors will talk with the patient about the risks of this treatment. They will also consider several other factors, such as the type of cancer, results of any previous treatment, and the patient’s age and general health.

There are 2 types of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, depending on the source of the replacement blood stem cells: allogeneic (ALLO) and autologous (AUTO). ALLO uses donated stem cells, while AUTO uses the patient’s own stem cells. For multiple myeloma, AUTO is more commonly used. ALLO is being studied in clinical trials. In both types, the goal is to destroy all of the cancer cells in the marrow, blood, and other parts of the body using high doses of chemotherapy (usually melphalan) and then allow replacement blood stem cells to create healthy bone marrow and restore the body's immune response.

Side effects depend on the type of transplant, your general health, and other factors. Learn more about the basics of bone marrow and stem cell transplant.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

Doctors may recommend radiation therapy for patients with bone pain when chemotherapy is not effective or to control pain. However, using radiation therapy is not an easy decision. In many instances, pain (especially back pain) is due to structural damage to the bone. Radiation therapy may not help relieve this type of pain and may affect the bone marrow's response to future treatment. Radiation therapy can be helpful in some situations, but for people with newly diagnosed myeloma, therapies using medication are preferred because of their greater effectiveness.

Side effects of radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished. Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Surgery

Surgery is not usually a treatment option for curing multiple myeloma, but it may be used to relieve specific symptoms. Surgery is used to treat bone disease, especially if there are fractures, and recent plasmacytomas, especially if they occur outside the bone. If surgery is recommended for you, talk with your health care team about the details of the surgery, including the recovery period. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, social, and financial effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative and supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative and supportive care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. It often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative and supportive care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy, to improve symptoms.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups for additional emotional support. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

Cancer care is often expensive, and navigating health insurance can be difficult. Ask your doctor or another member of your health care team about talking with a financial navigator or counselor who may be able to help with your financial concerns.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative and supportive care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Refractory myeloma

The disease is called relapsed and refractory myeloma if the cancer no longer responds to the most recent treatment. If this happens, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have experience in treating refractory myeloma. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan. Also, clinical trials can be an important option.

Sometimes, medications that have gone through advanced phases of clinical trials and are awaiting FDA approval are made more readily available to patients with refractory myeloma through FDA’s Expanded Access Clinical Trial Program. For example, daratumumab was first approved in 2015 to be used alone to treat relapsed and refractory myeloma after other treatments had failed. In 2016, the FDA approved the use of daratumumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or with bortezomib and dexamethasone to treat people who have already received at least 1 previous treatment. Since then, daratumumab has received 5 more approvals from the FDA and is now approved in combination with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone to treat newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma who may also receive an AUTO bone marrow/stem cell transplant. You may want to talk to your doctor about which treatments are being studied in clinical trials.

Learn more about getting a second opinion before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan.

For people with refractory myeloma, palliative and supportive care may also be important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

For many people, a diagnosis of relapsed or refractory myeloma is very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with your doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of your health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. It is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning, which is common with myeloma, despite recent advances in treatments and testing. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent myeloma or relapsed myeloma. If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatments described above, such as targeted therapy and chemotherapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Recent advances in newer therapies mean that the chances of effective treatment for relapsed myeloma are increasing.

Your doctor may also suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent or relapsed myeloma. There are multiple medications currently being researched in the late stages of clinical trials that have shown promise as treatments for recurrent or relapsed myeloma. See the Latest Research section for more information. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative and supportive care will also be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with relapsed myeloma sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from and a cure for myeloma are unlikely. The disease is still considered incurable despite recent progress. If the cancer cannot be controlled even with the newer treatments available, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

Planning for your future care and putting your wishes in writing is important, especially at this stage of disease. Then, your health care team and loved ones will know what you want, even if you are unable to make these decisions. Learn more about putting your health care wishes in writing.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with your doctor or a member of your palliative care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable options for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.