Nicholas R. Latimer is a Reader in Health Economics at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom, and a Yorkshire Cancer Research Senior Research Fellow. He researches statistical methods to make the best use of data when treatment switching happens in clinical trials. Janet Wale is Previous Chair of the Health Technology Assessment International Patient and Citizen Involvement Interest Group. As a patient advocate, she wants all individuals to have access to good, evidence-based data to inform their health choices. Deborah Collyar, President of Patient Advocates In Research, educates people about research and works to help translate discoveries into better results for patients.

What is treatment switching in clinical trials?

Before a new cancer treatment is available to people, it must be tested in clinical trials to show that it is safe and effective. Often, research includes randomized controlled trials (RCT). These clinical trials separate participants into 2 or more groups. One group gets the new treatment and the other group, called the “control group,” receives a standard treatment. Treatment switching, also called crossover, is where people in 1 clinical trial group start taking the treatment meant for another group.

Usually treatment switching means that people in the control group start taking a new drug. There are several situations in which treatment switching may happen. It could be a planned part of the study, where people switch to the experimental treatment if the cancer worsens. In some cases, a data monitoring committee may require that treatment switching be allowed because one group is faring much better than the other and it is unethical to continue to keep the groups separate. Sometimes, treatment switching is unplanned, and patients take the experimental treatment if they can get it. These are a few examples of ways treatment switching might happen.

It could be a planned part of the study, where people switch to the experimental treatment if the cancer worsens. In some cases, a data monitoring committee may require that treatment switching be allowed because one group is faring much better than the other and it is unethical to continue to keep the groups separate. Sometimes, treatment switching is unplanned, and patients take the experimental treatment if they can get it. These are a few examples of ways treatment switching might happen.

Does treatment switching in clinical trials affect cancer research?

Treatment switching can benefit clinical trial participants, but it may also affect how researchers interpret the trial’s results. In cancer clinical trials, researchers want to see if a new treatment stops cancer cells or delays their growth while increasing survival. But if people in the control group end up getting the new treatment, there really isn’t a control group anymore. If evaluating survival is the primary purpose of the study and the treatment switching is not planned, then the researchers may have a difficult time comparing the new treatment to the standard treatment.

Also, once new treatments are approved and available for patient use, governments and other payers need to decide if they should pay for them. To do this, experts evaluate the value of the new treatment, including its effectiveness in clinical trials, possible side effects or harms, and costs. Sometimes, treatment switching may make it harder to come to a conclusion.

What’s an example of how treatment switching impacts clinical trials?

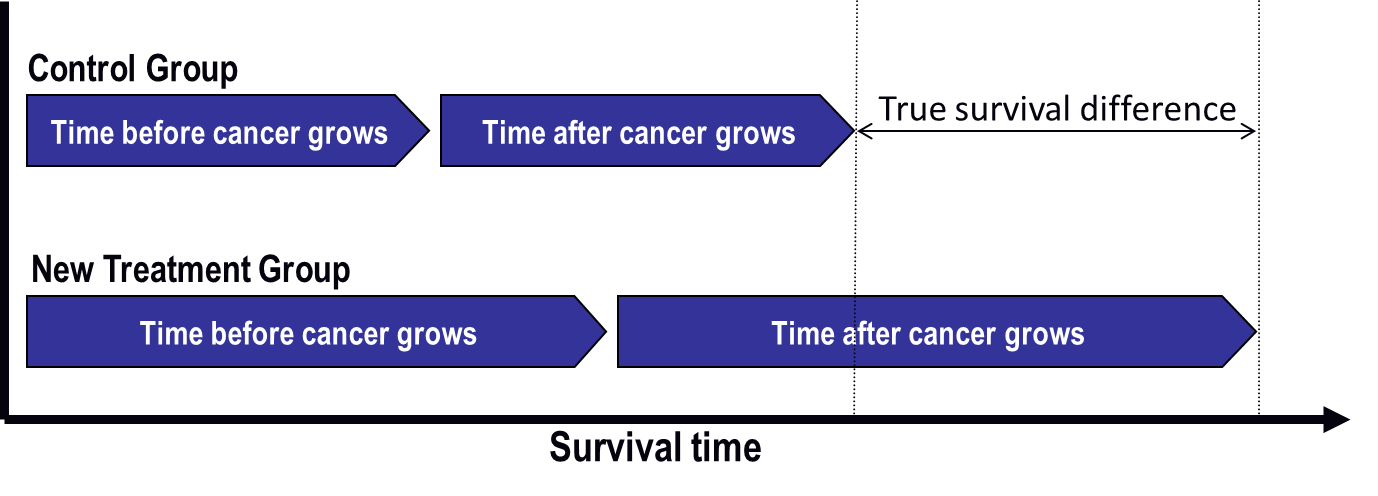

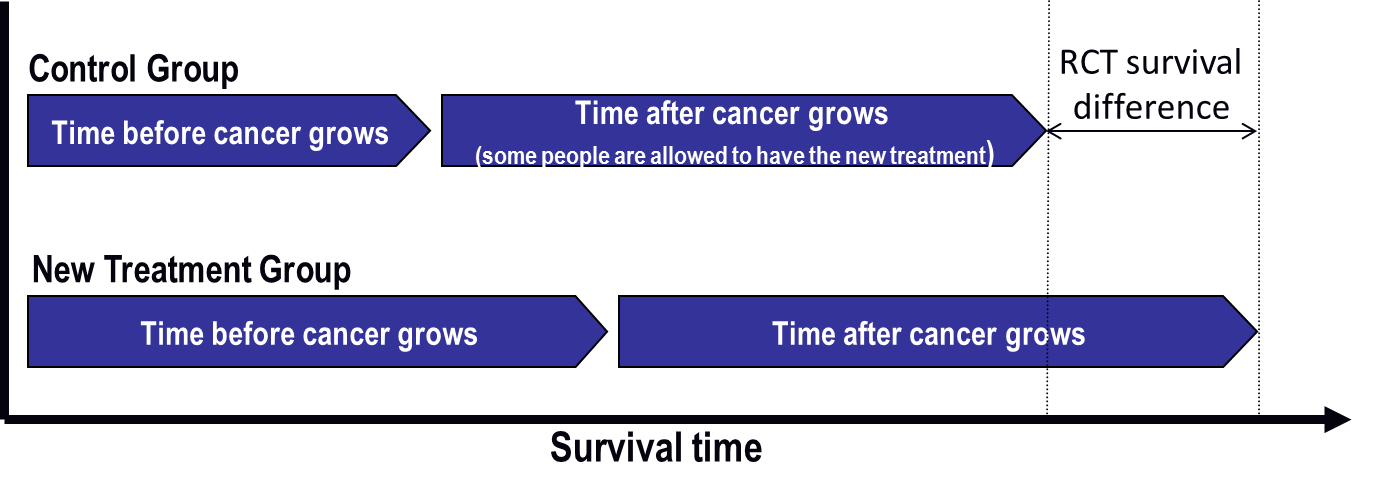

Figure 1 and Figure 2 below show an example of clinical trial results without and with switching by people in the control group once their cancer started growing again.

Figure 1: Results researchers want to see in a clinical trial of a new cancer treatment

Figure 2: What researchers might see in a clinical trial if treatment switching happens

The time before cancer grows is the same in each graph. In Figure 2, some people in the control group switch to the new treatment after their cancer starts growing again. The new treatment helps them, and their survival time increases.

The good thing is that everyone has the opportunity to benefit from the new drug. The drawback is that the overall survival difference between treatment groups is much less in Figure 2 than it is in Figure 1, where treatment switching was not allowed. This means the new treatment does not look as good as it actually is. The risk is that the treatment might not be approved for use and that future patients might not be able to receive the drug.

Can clinical trials be adjusted to account for treatment switching?

When treatment switching happens, researchers need to carefully adjust that clinical trial’s design or how they interpret its results, so the trial shows a more real effect. A lot of work has been done to find ways to estimate what the clinical trial results would have been if treatment switching hadn’t happened. These interpretations use complex mathematical models. Some governments and other funding decision-makers are happy to use these interpretations, but only if they are confident that the mathematical analysis has been done correctly. These analyses are complicated, not easy to do, and difficult to understand. But, with careful planning, they help show how a new treatment compares to standard treatment while having allowed participants to benefit from treatment switching.

Some analyses require a lot of information from people who take part in a clinical trial. For example, participants might have more blood tests. Or they might be asked to fill out multiple surveys on how their health changes over time. While this creates more work, it improves the chances that reliable adjustments for treatment switching can be made—and that decision-makers will use them.

What’s an example of how treatment switching interpretations have been used?

In one example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England investigated the effectiveness and value of a new targeted therapy medication for a type of skin cancer called melanoma. In the trial, more than 57% of people in the control group switched onto the new drug at some point during the trial. The trial results didn’t look useful until the results were statistically interpreted to account for treatment switching. Then they showed that the new drug could be almost twice as effective as the control treatment. As a result, that new targeted therapy was recommended for funding by NICE.

Is research continuing on treatment switching interpretations in clinical trials?

A lot of work has gone into showing how well statistical methods for interpreting study results can work in different settings. Researchers are learning how to make these methods clear, so decision-makers can trust them. Researchers in Australia are developing a checklist to help specify the steps researchers must take when they present interpretations of treatment switching.

What questions should I ask about treatment switching before I join a clinical trial?

If you’re considering being part of a clinical trial, ask if you’ll be allowed to switch treatments, so that you are clear on the rules of that clinical trial. You should also ask if extra information is being collected during the clinical trial so that the researchers can effectively account for treatment switching in the study results.