ON THIS PAGE: You will learn the basics about the different types of treatments doctors use for people with bladder cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known so far. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new or modified approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options, including clinical trials. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

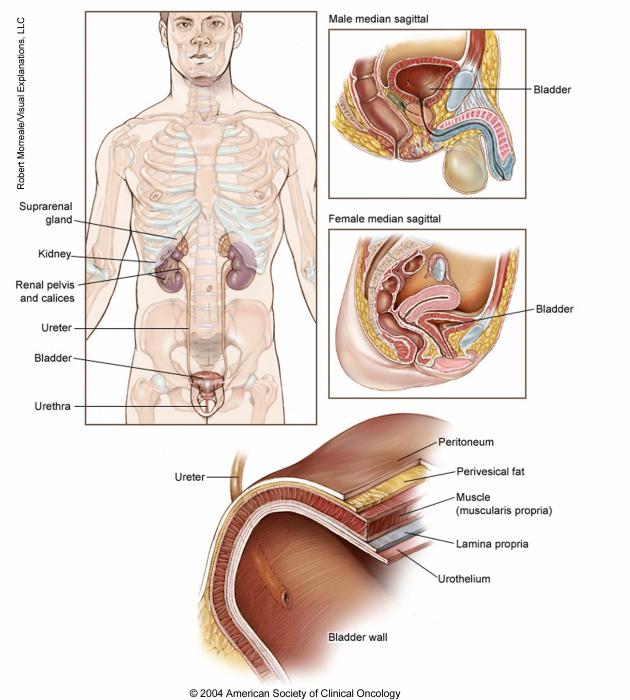

How bladder cancer is treated

Different people with bladder cancer have different needs that have to treated. The treatments that your doctor recommends in the treatment plan are chosen based on the characteristics of your diagnosis and your overall health, as well as other factors.

Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Also, talk about the goals of each treatment with your doctor and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for bladder cancer because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

To read an overview of treatment options based on the extent of the bladder cancer, read the next section in this guide, Treatments by Stage.

The most common types of treatments used for bladder cancer are described below. Your care plan also includes treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. There are different types of surgery for bladder cancer. Your health care team will recommend a specific surgery based on the stage and grade of the disease.

Transurethral bladder tumor resection (TURBT). This procedure is used for diagnosis and staging, as well as treatment. During TURBT, a surgeon inserts a cystoscope through the urethra into the bladder. The surgeon then removes the tumor using a tool with a small wire loop, a laser, or high-energy electricity, which is called fulguration. The patient is given an anesthetic, medication to block the awareness of pain, before the procedure begins.

For people with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, TURBT may be able to eliminate the cancer. However, the doctor may recommend additional treatments after TURBT to lower the risk of the cancer returning, such as intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (see below).

For people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, additional treatments involving surgery to remove the bladder or, less commonly, radiation therapy are usually recommended. Chemotherapy is commonly used in muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Radical cystectomy and lymph node dissection. A radical cystectomy is the removal of the whole bladder and possibly nearby tissues and organs. These organs may include the prostate and part of the urethra or the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and part of the vagina.

For all patients, lymph nodes in the pelvis are removed. This is called a pelvic lymph node dissection. An extended pelvic lymph node dissection is the most accurate way to find cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes.

In rare, very specific situations, it might be appropriate to remove only part of the bladder, which is called partial cystectomy. However, this surgery is not the standard of care for people with muscle-invasive disease.

During a laparoscopic or robotic cystectomy, the surgeon makes several small incisions, or cuts, instead of the 1 larger incision used for traditional open surgery. The surgeon then uses telescoping equipment with or without robotic assistance to remove the bladder. The surgeon must make an incision to remove the bladder and surrounding tissue. This type of operation requires a surgeon who is very experienced in this type of surgery. Your doctor can discuss these options with you and help you make an informed decision.

Urinary diversion. If the entire bladder is removed, the doctor will create a new way to pass urine out of the body. One way to do this is to use a section of the small intestine or colon to divert urine to a stoma or ostomy (an opening) on the outside of the body. The patient then must wear a bag attached to the stoma to collect and drain urine.

Surgeons can sometimes use part of the small or large intestine to make a urinary reservoir, which is a storage pouch that sits inside the body. With these procedures, the patient does not need a urinary bag. For some patients, the surgeon is able to connect the pouch to the urethra, creating what is called an orthotopic neobladder, so the patient can pass urine out of the body. However, the patient may need to insert a thin tube called a catheter if the neobladder is not fully emptied of urine. Also, patients with a neobladder will no longer have the urge to urinate and will need to learn to urinate on a consistent schedule. For other patients, an internal (inside the abdomen) pouch made of small and/or large intestine is created and connected to the skin on the abdomen or belly button (umbilicus) through a small stoma (an example is an "Indiana Pouch"). With this approach, patients do not need to wear a bag. Patients drain the internal pouch multiple times a day by inserting a catheter through the small stoma and immediately removing the catheter. Your health care team will help you adapt to these changes.

Side effects of bladder cancer surgery

Living without a bladder can affect a person's quality of life. Finding ways to keep all or part of the bladder is an important treatment goal. For some people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, treatment plans involving chemotherapy and radiation therapy after TURBT (see "Bladder preservation" in Treatments by Stage) may be used as an alternative to removing the bladder.

The side effects of bladder cancer surgery depend on the procedure. Research has shown that having a surgeon with expertise in bladder cancer can improve the outcome of people with bladder cancer. Patients should talk with their doctor in detail to understand exactly what side effects may occur, including urinary and sexual side effects, and how they can be managed. In general, side effects may include:

-

Prolonged healing time

-

Infection

-

Blood clots or bleeding

-

Discomfort after surgery and injury to nearby organs

-

Infections or urine leaks after cystectomy or a urinary diversion. If a neobladder has been created, a patient may sometimes be unable to urinate or completely empty the bladder.

-

The inability of a penis to become erect, called erectile dysfunction, after cystectomy. Sometimes, a nerve-sparing cystectomy can be performed. When this is done successfully, a normal erection may be possible.

-

Damage to nerves in the pelvis and loss of sexual feeling and orgasm

-

Risks due to anesthesia or other coexisting medical issues

-

Loss of stamina or physical strength for some time

-

Change in the acid-base balance in the body and low levels of vitamin B12

Before surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for bladder cancer include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Immunotherapy

-

Targeted therapy

-

Gene therapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects and interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, typically consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given the same day.

There are 2 types of chemotherapy that may be used to treat bladder cancer. The type the doctor recommends and when it is given depends on the stage of the cancer. Talk with your doctor about chemotherapy before or after surgery.

-

Intravesical chemotherapy. Intravesical, or local, chemotherapy is usually given by a urologist. During this type of therapy, drugs are delivered into the bladder through a catheter that has been inserted through the urethra. Local treatment only destroys superficial tumor cells that come in contact with the chemotherapy solution. It cannot reach tumor cells in the bladder wall or tumor cells that have spread to other organs. Mitomycin-C (available as a generic drug), gemcitabine (Gemzar), docetaxel (Taxotere), and valrubicin (Valstar) are the drugs used most often for intravesical chemotherapy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also approved mitomycin (Jelmyto) for treatment of low-grade upper tract urothelial cancer.

-

Systemic chemotherapy. The most common regimens for systemic, or whole-body, chemotherapy to treat bladder cancer include:

-

Cisplatin and gemcitabine

-

Carboplatin (available as a generic drug) and gemcitabine

-

MVAC, which combines 4 drugs: methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall), vinblastine (Velban), doxorubicin, and cisplatin

-

Dose-dense (DD)-MVAC with growth factor support: This is the same regimen as MVAC, but there is less time between treatments and has mostly replaced MVAC

-

Docetaxel or paclitaxel (available as a generic drug)

-

Pemetrexed (Alimta)

Many systemic chemotherapies continue to be tested in clinical trials to help find out which drugs or combinations of drugs work best to treat bladder cancer. Usually a combination of drugs works better than a single drug alone. Scientific evidence strongly supports the use of cisplatin-based chemotherapy before radical surgery for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. This is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

If platinum-based chemotherapy shrinks, slows, or stabilizes advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer, immunotherapy with avelumab (Bavencio, see "Immunotherapy" below) may be used to try to prevent or delay the cancer from coming back and to help people live longer. This is called switch maintenance treatment.

Side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual drug, combination regimen, and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, blood clots and bleeding, loss of appetite, taste changes, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, and diarrhea, among others. These side effects usually go away after treatment is finished.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells. It can be given locally or throughout the body.

Local immunotherapy

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). The standard immunotherapy drug for bladder cancer is a weakened mycobacterium called BCG, which is similar to the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. BCG is placed directly into the bladder through a catheter. This is called intravesical therapy. BCG attaches to the inside lining of the bladder and stimulates the immune system to destroy the tumor cells. BCG can cause flu-like symptoms, fevers, chills, fatigue, burning sensation in the bladder, and bleeding from the bladder, among others.

Interferon (Roferon-A, Intron A, Alferon). Interferon is another type of immunotherapy that may rarely be given as intravesical therapy. It is sometimes combined with BCG if using BCG alone does not help treat the cancer. Treatment with interferon is extremely uncommon nowadays.

Systemic immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (updated 04/2023). An active area of immunotherapy research is looking at drugs that block PD-1 and PD-L1. PD-1 is found on the surface of T cells, which are a type of white blood cell that directly helps the body’s immune system fight disease. Because PD-1 keeps the immune system from destroying cancer cells, stopping PD-1 from working allows the immune system to better eliminate the cancer.

-

Avelumab (Bavencio). If chemotherapy has slowed or shrunk advanced urothelial cancer, the PD-L1 inhibitor avelumab can be given after chemotherapy, regardless of whether the tumor expresses PD-L1, since it has been shown to lengthen life and lower the risk of the cancer worsening. This kind of treatment is called switch maintenance therapy. Avelumab can also be used to treat advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has not been stopped by platinum chemotherapy.

-

Nivolumab (Opdivo). Nivolumab is a PD-1 inhibitor that can be used to treat advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has not been stopped by platinum chemotherapy. It may also be given after complete surgical removal of the cancer, called adjuvant therapy, to lower the chance of it coming back in people who are at high risk of recurrence based on cancer stage.

-

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Pembrolizumab is a PD-1 inhibitor that can be used to treat bladder cancer in these situations:

-

Advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has not been stopped by platinum chemotherapy. It is the only immunotherapy that has been shown to help people in this situation live longer (compared to taxane or vinflunine chemotherapy).

-

In combination with enfortumab vedotin for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma among people who cannot receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

-

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Tis) that has not been stopped by BCG treatment in people who cannot receive or choose not to have radical cystectomy.

-

In the United States, people who cannot receive any platinum-based chemotherapy can receive pembrolizumab regardless of whether the tumor overexpresses PD-L1.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors continue to be studied in several clinical trials across all stages of bladder cancer.

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include fatigue, skin reactions (such as itching and rash), flu-like symptoms, thyroid gland function changes, hormonal and/or weight changes, diarrhea, and lung, liver, and gut inflammation, among others. Any body organ can be a target of an overactive immune system, so talk with your doctor about possible side effects for the immunotherapy recommended for you, so you know which changes to look for and can report them to the health care team early. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and tries to limit damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run genomic tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in your tumor. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective standard treatment and relevant clinical trials whenever possible. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Erdafitinib (Balversa). Erdafitinib is a drug given by mouth (orally) that is approved to treat people with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with particular FGFR3 or FGFR2 genetic changes that has continued to grow or spread during or after platinum chemotherapy. There is a specific FDA-approved companion test to find out who may benefit from treatment with erdafitinib.

Common side effects of erdafitinib may include increased phosphate level, mouth sores, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, dry mouth/skin, nails separating from the nail bed or poor nail formation, and change in appetite and taste, among others. Erdafitinib may also cause rare but serious eye problems, including retinopathy and epithelial detachment, which could cause blind spots that are called visual field defects. Evaluation by an ophthalmologist or optometrist is necessary at least every month in the first 4 months and then every 3 months after that time, along with frequent Amsler grid assessments at home.

Enfortumab vedotin-ejfv (Padcev) (updated 04/2023). Enfortumab vedotin-ejfv is approved to treat locally advanced (unresectable) or metastatic urothelial cancer in:

-

People who have already received a PD-1 or PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor (see “Immunotherapy,” above) and platinum-based chemotherapy

-

People who cannot receive cisplatin chemotherapy and have already received 1 or more treatments

-

Combination with pembrolizumab in people who cannot receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Enfortumab vedotin-ejfv is an antibody-drug conjugate that targets Nectin-4, which is present in urothelial cancer cells. Antibody-drug conjugates attach to targets on cancer cells and then release a small amount of cancer medication directly into the tumor cells. Common side effects of enfortumab vedotin-ejfv include fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, rash, hair loss, changes in appetite and taste, nausea, diarrhea, dry eye, itching, dry skin, and elevated blood sugar, among others.

Sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy). Sacituzumab govitecan is approved to treat locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has previously been treated with a platinum-based chemotherapy and a PD-1 or PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, which applies to many people with urothelial carcinoma. Like enfortumab vedotin-ejfv, sacituzumab govitecan is an antibody-drug conjugate but has a very different structure, components, and mechanism of action. Common side effects of sacituzumab govitecan may include low count of certain white blood cells (neutropenia), nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, hair loss, anemia, vomiting, constipation, decreased appetite, rash, abdominal pain, and a few other, less common effects.

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for a specific medication and how they can be managed.

Return to top

Gene therapy (updated 12/2022)

Gene therapy is a treatment that alters the genetic code of cells to make them do something new or to improve certain functions. It can be used to train the body’s immune system to find and destroy cancer cells or to protect cells from the side effects of cancer treatment. Gene therapy may be offered to people with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, including carcinoma in situ, that has not responded to BCG treatment. Nadofaragene firadenovec (Adstiladrin) is gene therapy that uses a virus that is unable to replicate itself. The therapy is given by urinary catheter into the bladder. The virus includes a gene called IFN alpha2b. When the virus enters the cells lining the bladder, it releases the gene, and the gene becomes part of the genetic makeup of the bladder cells. This new gene teaches the cells to make the interferon alpha2b protein, and this protein helps destroy cancer cells. The most common side effects of nadofaragene firadenovec include bladder discharge, fatigue, bladder spasms, increased urge to urinate, blood in the urine, chills, fever, and pain when urinating.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation therapy given from a machine outside the body. A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

Radiation therapy is usually not used by itself as a primary treatment for bladder cancer, but it is typically given in combination with systemic chemotherapy. Some people who cannot receive chemotherapy might receive radiation therapy alone. Combined radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be used to treat cancer that is located only in the bladder:

-

To destroy any cancer cells that may remain after TURBT, so all or part of the bladder does not have to be removed, when appropriate (see "Bladder preservation" in Treatments by Stage).

-

To relieve symptoms caused by a tumor, such as pain, bleeding, or blockage (called "palliative treatment," see section below).

Side effects from radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, and loose bowel movements. For bladder cancer, side effects most commonly occur in the pelvic or abdominal area and may include bladder irritation, with the need to pass urine frequently during the treatment period, and bleeding from the bladder or rectum; other side effects may occur less commonly. Most side effects tend to go away relatively soon after treatment is finished.

Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative care or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after an advanced cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to get rid of the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission is when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (regional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence, also known as metastasis).

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options.

In general, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancers that come back in the same location as the original tumor or somewhere else in the bladder may be treated in a similar way as the first cancer. However, if the cancer continues to return after treatment, radical cystectomy may be recommended. Bladder cancers that recur outside the bladder are more difficult to eliminate with surgery and are often treated with systemic medications, radiation therapy, or both. Your doctor may also suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent bladder cancer. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care can be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Full recovery from bladder cancer is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or metastatic.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, expertise, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is a specific type of palliative care designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with the health care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

Information about the cancer’s stage and grade will help the doctor recommend a specific treatment plan. The next section in this guide is Treatments by Stage. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.