ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use to treat people with kidney cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for kidney cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. Information in this section is based on medical standards of care for kidney cancer in the United States. Treatment options can vary from one place to another.

When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials offer additional options to consider. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How kidney cancer is treated

In cancer care, different types of doctors who specialize in cancer, called oncologists, often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. For kidney cancer, the health care team usually includes these specialists:

-

Urologist. A doctor who specializes in the genitourinary tract, which includes the kidneys, bladder, genitals, prostate, and testicles.

-

Urologic oncologist. A urologist who specializes in treating cancers of the urinary tract.

-

Medical oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with systemic treatments using medications.

-

Radiation oncologist. A doctor trained to treat cancer with radiation therapy. This doctor will be part of the team if radiation therapy is recommended.

Cancer care teams include other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, dietitians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and others. Learn more about the clinicians who provide cancer care.

Treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors, including the cell type and stage of cancer, possible side effects, and the patient’s preferences and overall health. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving treatment. These types of conversations are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is important for kidney cancer because there are different treatment options. Learn more about making treatment decisions.

Kidney cancer is most often treated with surgery, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of these treatments. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are occasionally used. People with kidney cancer that has spread, called metastatic cancer (see below), often receive multiple lines of therapies. This means treatments are given one after another.

The common types of treatments used for kidney cancer, as well as different disease states of kidney cancer, are described below. Your care plan also includes treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care.

READ MORE BELOW

Active surveillance

Sometimes, the doctor may recommend closely monitoring the tumor with regular diagnostic tests and clinic appointments. This is called "active surveillance." Active surveillance may be recommended in older adults and people who have a small renal tumor and other serious medical conditions, such as heart disease, chronic kidney disease, or severe lung disease. Younger people who have small kidney masses (smaller than 5 cm) may also be recommended to undergo active surveillance due to the low likelihood of the tumor spreading. Active surveillance may also be used for some people with kidney cancer as long as they are otherwise well and have few or no symptoms, even if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Systemic therapies (see "Therapies using medication," below) can be started if it looks like the disease is getting worse.

Active surveillance is not the same as "watchful waiting" for kidney cancer. While active surveillance uses interval diagnostic scans, watchful waiting involves regular appointments to review symptoms, but patients do not have regular diagnostic tests, such as biopsy or imaging scans. The doctor simply watches for symptoms. If symptoms suggest that action is needed, then a new treatment plan is considered.

Return to top

Surgery

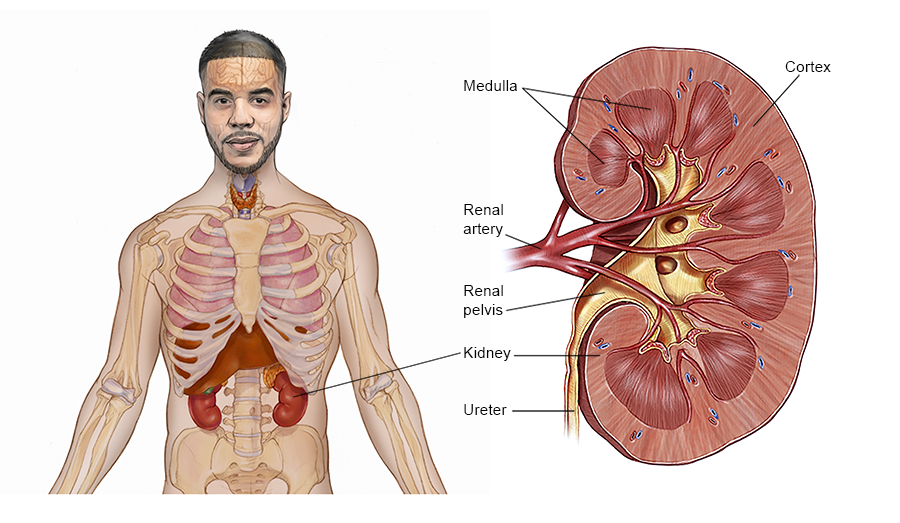

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. If the cancer has not spread beyond the kidneys, surgery to remove the tumor may be the only treatment needed. Surgery to remove the tumor may mean removing part or all of the kidney, as well as possibly nearby tissue and lymph nodes.

Types of surgery used for kidney cancer include the following procedures:

-

Radical nephrectomy. Surgery to remove the tumor, the entire kidney, and surrounding tissue is called a radical nephrectomy. If nearby tissue and surrounding lymph nodes are also affected by the disease, a radical nephrectomy and lymph node dissection is performed. During a lymph node dissection, the lymph nodes affected by the cancer are removed. If the cancer has spread to the adrenal gland or nearby blood vessels, the surgeon may remove the adrenal gland during a procedure called an adrenalectomy, as well as parts of the blood vessels. A radical nephrectomy is usually recommended to treat a large tumor when there is not much healthy tissue remaining. Sometimes the renal tumor will grow directly inside the renal vein and enter the vena cava on its way to the heart. If this happens, complex cardiovascular surgical techniques are needed.

-

Partial nephrectomy. A partial nephrectomy is the surgical removal of the tumor. This type of surgery preserves kidney function and lowers the risk of developing chronic kidney disease after surgery. Research has shown that partial nephrectomy is effective for T1 tumors whenever surgery is possible. Newer approaches that use a smaller surgical incision, or cut, are associated with fewer side effects and a faster recovery.

-

Laparoscopic and robotic surgery (minimally invasive surgery). During laparoscopic surgery, the surgeon makes several small cuts in the abdomen, rather than the one larger cut used during a traditional surgical procedure. The surgeon then inserts telescoping equipment into these small keyhole incisions to completely remove the kidney or perform a partial nephrectomy. Sometimes, the surgeon may use robotic instruments to perform the operation. This surgery may take longer but may be less painful. Laparoscopic and robotic approaches require specialized training. It is important to discuss the potential benefits and risks of these types of surgery with your surgical team and to be certain that the team has experience with the procedure.

-

Cytoreductive nephrectomy. A cytoreductive nephrectomy is the surgical removal of the primary kidney tumor along with the whole kidney in cases where disease has spread beyond the kidney. This may be recommended after diagnosis or after other systemic treatments have already been started. There is growing evidence that in metastatic disease, starting systemic treatments first is helpful. There are ongoing clinical trials evaluating the when is the best time for cytoreductive nephrectomy after treatment with immunotherapy (see below).

-

Metastasectomy. Metastasectomy is the surgical removal of a single site of disease, such as lung, pancreas, liver, or other site, with the goal of curing the cancer. This surgery is generally recommended for people who will benefit from removal of a single site of kidney cancer spread.

Before any type of surgery, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Return to top

Non-surgical tumor treatments

Sometimes surgery is not recommended because of characteristics of the tumor or the patient’s overall health. Every patient should have a thorough conversation with their doctor about their diagnosis and risk factors to see if these treatments are appropriate and safe for them. The following procedures may be options:

-

Radiofrequency ablation. During radiofrequency ablation (RFA), a needle is inserted into the tumor to destroy the cancer with an electric current. The procedure is performed by an interventional radiologist or urologist. The patient is sedated and given local anesthesia to numb the area. In the past, RFA has only been used for people who were too sick to have surgery. Today, most patients who are too sick for surgery are monitored with active surveillance instead (see above), and patients who have locally advanced disease may also be recommended to have systemic treatments (see below).

-

Cryoablation. During cryoablation, also called cryotherapy or cryosurgery, a metal probe is inserted through a small incision into cancerous tissue to freeze the cancer cells. A computed tomography (CT) scan and ultrasound are used to guide the probe. Cryoablation requires general anesthesia for several hours and is performed by an interventional radiologist. Some surgeons combine this technique with laparoscopy to treat the tumor, but there is not much long-term research evidence to prove that it is effective.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Systemic medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications to take at home, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for kidney cancer include:

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunotherapy

-

Chemotherapy

Each of these types of therapies is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. Research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

Targeted therapies for kidney cancer are described below.

Anti-angiogenesis therapy. This type of treatment focuses on stopping angiogenesis, which is the process of making new blood vessels. Most clear cell kidney cancers have mutations of the VHL gene, which causes the cancer to make too much of a certain protein, known as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF controls the formation of new blood vessels and can be blocked with certain drugs. Because a tumor needs the nutrients delivered by blood vessels to grow and spread, the goal of anti-angiogenesis therapies is to “starve” the tumor. There are 2 ways to block VEGF, with small molecule inhibitors of the VEGF receptors (VEGFR) or with antibodies directed against these receptors.

-

Bevacizumab (Avastin). Bevacizumab is an antibody that has been shown to slow tumor growth for people with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Bevacizumab combined with interferon (see “Immunotherapy,” below) slows tumor growth and spread. There are 2 similar drugs, called bevacizumab-awwb (Mvasi) and bevacizumab-bvzr (Zirabev), that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of metastatic kidney cancer. These are called biosimilars, and they are similar in their action to the original bevacizumab antibody.

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Axitinib (Inlyta), cabozantinib (Cabometyx), pazopanib (Votrient), lenvatinib (Lenvima), sorafenib (Nexavar), sunitinib (Sutent), and tivozanib (Fotivda) are TKIs that block VEGF receptors. They may be used to treat clear cell kidney cancer. Of these approved treatments, pazopanib, sunitinib, or cabozantinib are often used as first-line treatments. Axitinib or cabozantinib may be used as first-line treatments combined with immunotherapies (see below). After first-line treatment, axitinib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, and tivozanib may be recommended, if they have not already been used.

mTOR inhibitors. Everolimus (Afinitor) and temsirolimus (Torisel) are drugs that target a certain protein that helps kidney cancer cells grow, called mTOR. Studies show that these drugs slow kidney cancer growth. Everolimus may be prescribed in combination with the anti-angiogenesis drugs lenvatinib or bevacizumab.

HIF2a inhibitor (updated 12/2023). Belzutifan (Welireg) is a drug that targets hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha (HIF2a), which is a protein that can support the growth of blood vessels and cancer cells. Belzutifan can be used to treat kidney cancer in people with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome as well as in people who have advanced kidney cancer that has progressed after previous treatments with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (see below) and a blood vessel blocker.

Combining anti-angiogenesis inhibitors and immunotherapy. There are 4 approved combination treatments for the first treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma.

-

Axitinib and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), which is an immune checkpoint inhibitor (see "Immunotherapy," below)

-

Axitinib and avelumab (Bavencio), which is another immune checkpoint inhibitor

-

Cabozantinib (an anti-angiogenesis therapy) with nivolumab (Opdivo), another immune checkpoint inhibitor

-

Lenvatinib (also an anti-angiogenesis therapy) with pembrolizumab

While all of these combination treatments were approved based on outcomes that were better than treatment with sunitinib, none of the combinations have been compared directly to each other. Therefore, the doctor will help select the most appropriate treatment option for each patient based on their unique situation.

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for each specific medication and how they can be managed.

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells. Different immunotherapies for kidney cancer are described below.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2, Proleukin). IL-2 is a type of immunotherapy that has been used to treat later-stage kidney cancer. IL-2 is a cytokine, which is a protein produced by white blood cells, and is important in immune system function, including the destruction of tumor cells.

High-dose IL-2 can cause severe side effects, such as low blood pressure, excess fluid in the lungs, kidney damage, heart attack, bleeding, chills, and fever. Patients may need to stay in the hospital for up to 10 days during treatment. However, some symptoms may be reversible. Only centers with expertise in high-dose IL-2 treatment for kidney cancer should recommend IL-2. High-dose IL-2 can cure a small percentage of people with metastatic kidney cancer. Some centers use low-dose IL-2 because it has fewer side effects, but it is not as effective.

Alpha-interferon. Alpha-interferon is used to treat kidney cancer that has spread. Interferon appears to change the proteins on the surface of cancer cells and slow their growth. Although it has not proven to be as beneficial as IL-2, alpha-interferon has been shown to lengthen lives when compared with an older treatment called megestrol acetate (Megace).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors. A type of immunotherapy called immune checkpoint inhibitors is continually being studied in kidney cancer. The FDA has approved the following treatments using immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of kidney cancer:

-

Nivolumab (Opdivo) and ipilimumab (Yervoy) for certain patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma that has not been previously treated.

-

Nivolumab in combination with cabozantinib (see “Anti-angiogenesis therapy,” above) as a first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma.

-

Avelumab (Bavencio) plus axitinib (see "Targeted Therapy," above) as a first-line treatment for people with advanced renal cell carcinoma.

-

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus axitinib as a first-line treatment for people with advanced renal cell carcinoma.

-

Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib (see "Targeted Therapy," above) as a first-line treatment for people with advanced renal cell carcinoma.

-

Pembrolizumab alone for renal cell carcinoma with an increased risk of recurrence after nephrectomy or after surgical removal of sites of metastasis.

The FDA approvals for advanced renal cell carcinoma were based on large clinical trials showing the benefit of the immunotherapy combinations compared to sunitinib in people with advanced or metastatic kidney cancer. Additional research had previously shown that nivolumab given as a single drug through the vein every 2 weeks also helped certain people who had previously received anti-angiogenesis treatments live longer than patients treated with the targeted therapy everolimus. The FDA approval for pembrolizumab following surgery was based on a large clinical trial that showed improvement in time to recurrence for people who had received surgery for the primary kidney tumor or all sites of distant spread. There are several ongoing clinical trials investigating immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of kidney cancer (see Latest Research).

Different types of immunotherapy can cause different side effects. Common side effects include skin reactions, flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, and weight changes. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects for the immunotherapy recommended for you. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time.

Although chemotherapy is useful for treating many types of cancer, most cases of kidney cancer are resistant to chemotherapy. Researchers continue to study new drugs and new combinations of drugs. For some patients, the combination of gemcitabine (Gemzar) with capecitabine (Xeloda) or fluorouracil (5-FU) will temporarily shrink a tumor.

It is important to remember that transitional cell carcinoma, also called urothelial carcinoma, collecting duct carcinoma, renal medullary cancer, and Wilms tumor are all much more likely to be treated with chemotherapy.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These side effects usually go away after treatment is finished.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist.

Radiation therapy is not generally preferred as a primary treatment for kidney cancer. It is very rarely used alone to treat kidney cancer but can be used to increase the effects of systemic treatments using medication (see above). Radiation therapy is used mostly if a patient cannot have surgery and usually on areas where the cancer has spread and not on the primary kidney tumor. Most often, radiation therapy is used when the cancer has spread (see "Metastatic kidney cancer," below). This is done to help ease symptoms, such as bone pain or swelling in the brain.

Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, social, and financial effects of cancer

Cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative and supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Palliative and supportive care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive palliative and supportive care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments, such as surgery or radiation therapy, to improve symptoms.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and palliative and supportive care options. Many patients also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

Cancer care is often expensive, and navigating health insurance can be difficult. Ask your doctor or another member of your health care team about talking with a financial navigator or counselor who may be able to help with your financial concerns.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about palliative and supportive care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Metastatic kidney cancer

If cancer spreads to another part in the body from where it started, doctors call it metastatic cancer.

Metastatic kidney cancer most commonly spreads to the lungs, but it can also spread to the lymph nodes, bones, liver, brain, skin, and other areas in the body. This is a systemic disease that usually requires treatment with systemic therapy, such as targeted therapy or immunotherapy (described above).

For certain patients with metastatic kidney cancer who meet very specific criteria, active surveillance may be recommended.

Currently, the most effective treatments for metastatic kidney cancer include combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors that activate the immune system to attack cancer cells or an immune checkpoint inhibitor combined with a targeted treatment with a TKI. However, in some cases, an immune checkpoint inhibitor or a TKI may be given alone. These drugs have been shown to lengthen life when compared with standard treatment.

Sometimes, doctors may ask a surgeon to remove the kidney with the tumor in an operation called a cytoreductive nephrectomy (see above). The goal of this surgery is to help people live longer and can also treat pain or bleeding. Cytoreductive surgery may be recommended for certain patients before starting systemic treatment.

For kidney cancer that has spread to a limited number of locations, such as a single spot in the lung, surgery may be able to completely remove the cancer. This operation is called a metastasectomy (see above), and it can help some people delay or avoid the need for systemic therapy using medications. Other localized treatment options for distant tumors include RFA, cryoablation, and radiation therapy.

If the cancer has spread to many areas beyond the kidney, it is more difficult to treat with local treatments and systemic therapy may be given instead. If the cancer has spread to the bones, the cancer may be treated with radiation therapy, and medications to prevent bone loss or fractures should be recommended. If the cancer has spread to the brain, the tumors may be treated with radiation therapy, surgery, or both. If the cancer has spread, it is a good idea to talk with doctors who have a lot of experience in treating it. Doctors can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan, and the best treatment for you requires a collaborative approach. Clinical trials might also be an option. Learn more about getting a second opinion before starting treatment, so you are comfortable with your chosen treatment plan. Palliative and supportive care is also important to help relieve symptoms and side effects.

For many people, a diagnosis of metastatic cancer is very stressful and difficult. You and your family are encouraged to talk about how you feel with doctors, nurses, social workers, or other members of your health care team. It may also be helpful to talk with other patients, such as through a support group or other peer support program, or to meet with a mental health professional who has specific training in cancer.

This information is based on the ASCO guideline, "Management of Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma." Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Return to top

Remission and the chance of recurrence

A remission occurs when cancer cannot be detected in the body and there are no symptoms. This may also be called having “no evidence of disease” or NED.

A remission may be temporary or permanent. This uncertainty causes many people to worry that the cancer will come back. While many remissions are permanent, it is important to talk with your doctor about the possibility of the cancer returning. Understanding your risk of recurrence and the treatment options may help you feel more prepared if the cancer does return. Learn more about coping with the fear of recurrence.

If the cancer returns after the original treatment, it is called recurrent cancer. It may come back in the same place (called a local recurrence), nearby (regional recurrence), or in another place (distant recurrence). If you have had a partial nephrectomy already, a new tumor may form in the same kidney. The recurrent tumor can be removed with another partial nephrectomy or with a radical nephrectomy (see "Surgery," above).

If there is a recurrence, a new cycle of testing will begin to learn as much as possible about it. After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. Often the treatment plan will include the treatments described above, such as surgery, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy, but they may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. Your doctor may also suggest clinical trials that are studying newly developed systemic therapies or new combinations of these medications. Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative and supportive care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects.

People with recurrent cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Return to top

If treatment does not work

Recovery from cancer is not always possible. If the cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

This diagnosis is stressful, and for some people, advanced cancer is difficult to discuss. However, it is important to have open and honest conversations with your health care team to express your feelings, preferences, and concerns. The health care team has special skills, experience, and knowledge to support patients and their families and is there to help. Making sure a person is physically comfortable, free from pain, and emotionally supported is extremely important.

Planning for your future care and putting your wishes in writing is important, especially at this stage of disease. Then, your health care team and loved ones will know what you want, even if you are unable to make these decisions. Learn more about putting your health care wishes in writing.

People who have advanced cancer and who are expected to live less than 6 months may want to consider hospice care. Hospice care is designed to provide the best possible quality of life for people who are near the end of life. You and your family are encouraged to talk with your doctor or a member of your palliative care team about hospice care options, which include hospice care at home, a special hospice center, or other health care locations. Nursing care and special equipment can make staying at home a workable option for many families. Learn more about advanced cancer care planning.

After the death of a loved one, many people need support to help them cope with the loss. Learn more about grief and loss.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.