ON THIS PAGE: You will learn about the different types of treatments doctors use for people with breast cancer. Use the menu to see other pages.

This section explains the types of treatments, also known as therapies, that are the standard of care for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, you are encouraged to discuss with your doctor whether clinical trials are an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors learn through clinical trials whether a new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug and how often it should be given, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments. Some clinical trials also test giving less drug or radiation treatment or doing less extensive surgery than what is usually done as the standard of care. Clinical trials are an option for all stages of cancer. Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. Learn more about clinical trials in the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections of this guide.

How breast cancer is treated

In cancer care, doctors specializing in different areas of cancer treatment—such as surgery, radiation oncology, and medical oncology—work together with radiologists and pathologists to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, genetic counselors, nutritionists, therapists, and others. For people older than 65, a geriatric oncologist or geriatrician may also be involved in their care. Ask the members of your treatment team who is the primary contact for questions about scheduling and treatment, who is in charge during different parts of treatment, how they communicate across teams, and whether there is 1 contact who can help with communication across specialties, such as a nurse navigator. This can change over time as your health care needs change.

A treatment plan is a summary of your cancer and the planned cancer treatment. It is meant to give basic information about your medical history to any doctors who will care for you during your lifetime. Before treatment begins, ask your doctor for a copy of your treatment plan. You can also provide your doctor with a copy of the ASCO Treatment Plan form to fill out.

The biology and behavior of breast cancer affects the treatment plan. Some tumors are smaller but grow quickly, while others are larger and grow slowly. Treatment options and recommendations are very personalized and depend on several factors, including:

-

The tumor’s subtype, including hormone receptor status (ER, PR), HER2 status, and nodal status (see Introduction)

-

The stage of the tumor

-

Genomic tests, such as the multigene panels Oncotype DX™ or MammaPrint™, if appropriate (See Diagnosis)

-

The patient’s age, general health, menopausal status, and preferences

-

The presence of known mutations in inherited breast cancer genes, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2, based on results of genetic tests

Even though the breast cancer care team will specifically tailor the treatment for each patient and tumor, called "personalized medicine," there are some general steps for treating early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer.

For both ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and early-stage invasive breast cancer, doctors generally recommend surgery to remove the tumor. To make sure that the entire tumor is removed, the surgeon will also remove a small area of healthy tissue around the tumor, called a margin. Although the goal of surgery is to remove all of the visible cancer in the breast, microscopic cells can be left behind. In some situations, this means that another surgery could be needed to remove remaining cancer cells. There are different ways to check for microscopic cells that will ensure a clean margin. It is also possible for microscopic cells to be present outside of the breast, which is why systemic treatment with medication is often recommended after surgery, as described below.

For larger cancers, or those that are growing more quickly, doctors may recommend systemic treatment with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and/or hormonal therapy before surgery, called neoadjuvant therapy. There may be several benefits to having drug treatments before surgery:

-

Surgery may be easier to perform because the tumor is smaller.

-

Your doctor may find out if certain treatments work well for the cancer.

-

You may be able to try a new treatment through a clinical trial.

-

If you have any microscopic distant disease, it will be treated earlier by the drug therapy that circulates through the body.

-

People who may have needed a mastectomy could have breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) if the tumor shrinks enough before surgery.

After surgery, the next step in managing early-stage breast cancer is to lower the risk of recurrence and to try to get rid of any remaining cancer cells in the body. These cancer cells are undetectable with current tests but are believed to be responsible for a cancer recurrence, as they can grow over time. Treatment given after surgery is called "adjuvant therapy." Adjuvant therapies may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and/or hormonal therapy (see below for more information on each of these treatments).

Whether adjuvant therapy is needed depends on the chance that any cancer cells remain in the breast or the body and the chance that a specific treatment will work to treat the cancer. Although adjuvant therapy lowers the risk of recurrence, it does not completely get rid of the risk.

Along with staging, other tools can help estimate prognosis and help you and your doctor make decisions about adjuvant therapy. Depending on the subtype of breast cancer, this includes tests that can predict the risk of recurrence by testing your tumor tissue (such as Oncotype Dx™ or MammaPrint™; see Diagnosis). Such tests may also help your doctor better understand whether chemotherapy will help reduce the risk of recurrence.

If surgery to remove the cancer is not possible, it is called inoperable. The doctor will then recommend treating the cancer in other ways. Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, and/or hormonal therapy may be given to shrink the cancer.

For recurrent cancer, treatment options depend on how the cancer was first treated and the characteristics of the cancer mentioned above, such as ER, PR, and HER2.

Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. These types of talks are called “shared decision-making.” Shared decision-making is when you and your doctors work together to choose treatments that fit the goals of your care. Shared decision-making is particularly important for people with breast cancer because there are different treatment options. It is also important to check with your health insurance company before any treatment begins to make sure the planned treatment is covered.

People older than 65 may benefit from having a geriatric assessment before planning treatment. Find out what a geriatric assessment involves and how it can help people older than 65 with cancer.

Learn more about making treatment decisions.

The common types of treatments used for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer are described below. Your care plan also includes treatment for symptoms and side effects, which is an important part of cancer care.

Surgery

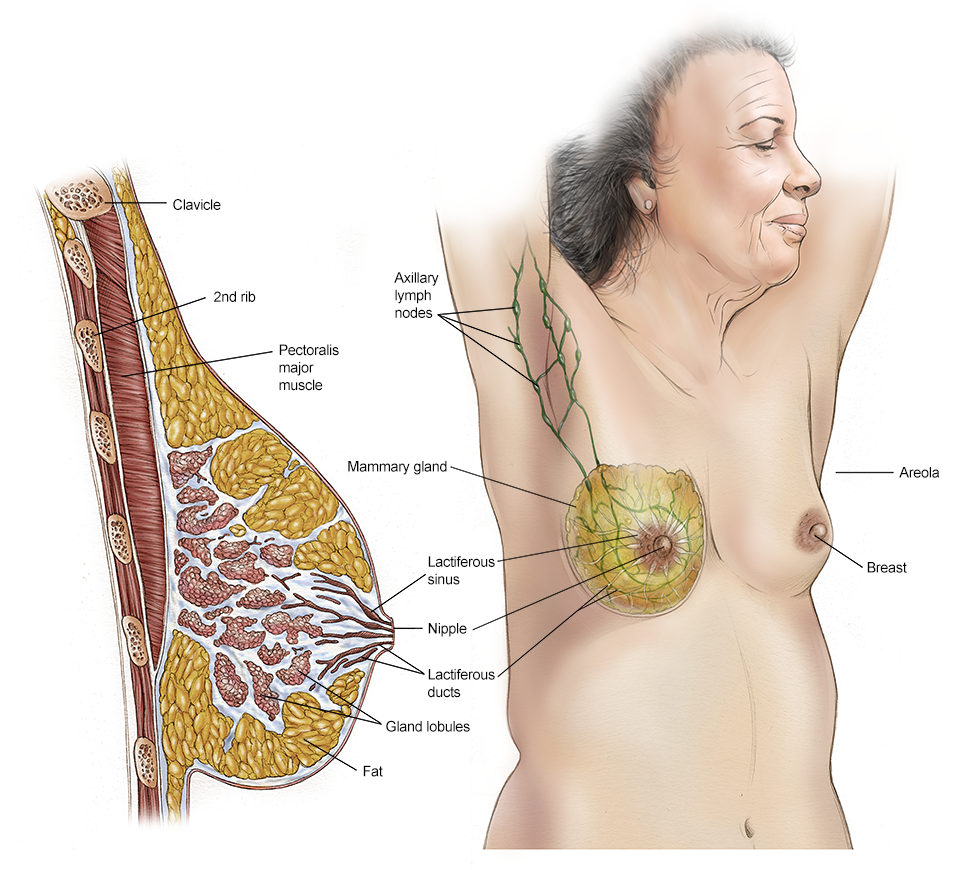

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. Surgery is also used to examine the nearby axillary lymph nodes, which are under the arm. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with surgery. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

The choice of surgery does not affect whether you will need therapy using medication, such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and/or targeted therapy (see below). Drug therapies are given based on the characteristics of the tumor, not the type of surgery you have.

Generally, the smaller the tumor, the more surgical options a patient has. The types of surgery for breast cancer include the following:

-

Lumpectomy. This is the removal of the tumor and a small, cancer-free margin of healthy tissue around the tumor. Most of the breast remains. For invasive cancer, radiation therapy to the remaining breast tissue is often recommended after surgery, especially for younger patients, patients with hormone receptor-negative tumors, and patients with larger tumors. For DCIS, radiation therapy after surgery is usually given. A lumpectomy may also be called breast-conserving surgery, a partial mastectomy, a quadrantectomy, or a segmental mastectomy.

-

Mastectomy. This is the surgical removal of the entire breast. There are several types of mastectomies. Talk with your doctor about whether the skin can be preserved, called a skin-sparing mastectomy, or whether the nipple can be preserved, called a nipple-sparing mastectomy or total skin-sparing mastectomy. Your doctor will also consider how large the tumor is compared to the size of your breast in determining the best type of surgery for you. Radiation therapy may be recommended following mastectomy. Learn more about the different types of mastectomies and exercising after a mastectomy.

Lymph node removal, analysis, and treatment

Cancer cells can be found in the axillary lymph nodes in some cancers. Knowing whether any of the lymph nodes near the breast contain cancer can provide useful information to determine treatment and prognosis.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy. In a sentinel lymph node biopsy (also called a sentinel node biopsy or SNB), the surgeon finds and removes 1 to 3 or more lymph nodes from under the arm that receive lymph drainage from the breast. This procedure is generally not an option when the doctor already knows based on clinical evaluation that the lymph nodes have cancer. Rather, it may be an option for patients with no obvious clinical evidence of lymph node involvement. This procedure helps avoid removing a larger number of lymph nodes with an axillary lymph node dissection (see below) for patients whose sentinel lymph nodes are mostly free of cancer. The smaller lymph node procedure helps lower the risk of several possible side effects. Those side effects include swelling of the arm called lymphedema, numbness, and arm movement and range of motion problems with the shoulder. These can be long-lasting issues that can severely affect a person’s quality of life. Importantly, the risk of lymphedema increases with the number of lymph nodes and lymph vessels that are removed or damaged during cancer treatment. This means that people who have a sentinel lymph node biopsy are less likely to develop lymphedema than those who have an axillary lymph node dissection (see below).

Your doctor may recommend imaging of your lymph nodes with an ultrasound and/or an image-guided biopsy of the lymph nodes before a sentinel lymph node biopsy to find out if the cancer has spread there (see Diagnosis). This is often done if you have a large cancer, if your lymph nodes can be felt during clinical examination, or if you are having treatment with chemotherapy before surgery. However, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) does not recommend doing this if your cancer is small and your lymph nodes are not able to be felt during clinical examination.

To find the sentinel lymph node, the surgeon usually injects a radioactive tracer and sometimes a dye behind or around the nipple. The injection, which can cause some discomfort, lasts about 15 seconds. The dye or tracer travels to the lymph nodes, arriving at the sentinel node first. If a radioactive tracer is used, it will give off radiation which helps the surgeon find the lymph node. If dye is used, the surgeon can find the lymph node when it turns a blue color.

The pathologist then examines the lymph nodes for cancer cells. If the sentinel lymph node(s) are cancer-free, research has shown that it is likely that the remaining lymph nodes will also be free of cancer. This means that no more lymph nodes need to be removed. If cancer is found in the sentinel lymph node, whether additional surgery is needed to remove more lymph nodes depends on the specific situation. For example, if only 1 or 2 sentinel lymph nodes have cancer and you plan to have a lumpectomy and radiation therapy to the entire breast, an axillary lymph node dissection may not be needed.

In general, for many people with early-stage breast cancer with tumors that can be removed with surgery and whose underarm lymph nodes are not enlarged, sentinel lymph node biopsy is the standard of care. However, in certain situations, it may be appropriate to not undergo any axillary surgery. You should talk with your surgeon about whether this may be the right approach for you.

- Axillary lymph node dissection. In an axillary lymph node dissection, the surgeon removes many lymph nodes from under the arm. These are then examined for cancer cells by a pathologist. The actual number of lymph nodes removed varies from person to person. People having a lumpectomy and radiation therapy who have a smaller tumor and 2 or fewer sentinel lymph nodes with cancer may avoid a full axillary lymph node dissection. This helps reduce the risk of side effects and does not decrease survival.

Usually, the lymph nodes are not evaluated for people with DCIS and no invasive cancer, since the risk of spread is very low. However, for patients diagnosed with DCIS who choose to have or need a mastectomy, the surgeon may consider a sentinel lymph node biopsy. If some invasive cancer is found with DCIS during the mastectomy, which happens occasionally, the lymph nodes may then need to be evaluated. However, a sentinel lymph node biopsy generally cannot be performed if the breast has already been removed with mastectomy. In that situation, an axillary lymph node dissection may be recommended.

Most people with invasive breast cancer will have either a sentinel lymph node biopsy or an axillary lymph node dissection. For most people younger than 70 with early-stage breast cancer, a sentinel lymph node biopsy will be used to determine if there is cancer in the axillary lymph nodes, since this information is used to make decisions about treatment. Many patients 70 and older with small hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative tumors in the breast and no clinically apparent cancer in the lymph nodes can avoid a lymph node evaluation, as the results may not change recommendations for therapies using medication or radiation therapy. Patients age 70 and older with larger hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative tumors, with other types of breast cancer, or with clinically apparent lymph nodes will generally be recommended to have evaluation of their axillary lymph nodes. Patients should talk with their doctor about recommendations for their specific situation.

No chemotherapy before surgery, and no cancer in the sentinel lymph nodes. For most people in this situation, ASCO does not recommend an axillary lymph node dissection. A small group of patients with tumors located in specific places or with high-risk features may be offered radiation therapy to the lymph nodes.

No chemotherapy before surgery, but there is cancer in the sentinel lymph nodes. If there is cancer in 1 to 2 sentinel lymph nodes, then additional nodal surgery can generally be avoided if the patient is planning to undergo a lumpectomy and receive radiation. If there is cancer in 3 or more sentinel lymph nodes, then ASCO recommends additional nodal surgery.

Chemotherapy is given before surgery. Treatment for people who have received chemotherapy before surgery depends on whether the chemotherapy has destroyed the cancer in the lymph nodes. Therefore, after chemotherapy, patients are often re-staged by sentinel lymph node biopsy. However, this is not always the case. If imaging scans or physical exams suggest abnormal lymph nodes are present, the patient should have an axillary lymph node dissection instead.

-

If there was no evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes either before or after chemotherapy, radiation therapy to the lymph node area is not recommended.

-

If there was evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes before chemotherapy and there is no longer evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes after chemotherapy, radiation therapy to the lymph node area is recommended.

-

If there is evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes after chemotherapy, then both an axillary lymph node dissection and radiation therapy to the lymph node area are recommended.

This information is based on the Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) and ASCO guideline, “Management of the Axilla in Early-Stage Breast Cancer.” Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Reconstructive (plastic) surgery

Patients who have a mastectomy or lumpectomy may want to consider breast reconstruction. This is surgery to recreate a breast using either tissue taken from another part of the body or synthetic implants. Reconstruction is usually performed by a plastic surgeon. A reconstruction done at the same time as the mastectomy is called immediate reconstruction. You may also have this surgery done at some point in the future, called delayed reconstruction.

For some patients undergoing a lumpectomy, reconstruction to keep both breasts looking similar is called oncoplastic surgery. This type of surgery may be performed by the breast surgeon.

The techniques discussed below are typically used to shape a new breast.

Implants. A breast implant uses saline-filled or silicone gel-filled forms to reshape the breast. The outside of a saline-filled implant is made up of silicone, and it is filled with sterile saline, which is salt water. Silicone gel-filled implants are filled with silicone instead of saline. There were prior concerns raised that silicone implants might be associated with connective tissue disorders, but clear evidence of this has not been found. Before having permanent implants, a patient may temporarily have a tissue expander placed that will create the correct-sized pocket for the implant. Implants can be placed above or below the pectoralis muscle. Talk with your doctor about the benefits and risks of silicone versus saline implants, and the placement of the implant. The lifespan of an implant depends on the individual. However, some people never need to have them replaced. Other important factors to consider when choosing implants include:

-

Saline implants sometimes "ripple" at the top or shift with time, but many people do not find it bothersome enough to replace.

-

Saline implants feel different than silicone implants. They are often firmer to the touch than silicone implants. If overfilled, they can be firmer, but they can also feel squishier if underfilled.

There can be problems with breast implants. Some people have problems with the shape or appearance. The implants can rupture or break, cause pain and scar tissue around the implant, or get infected. Implants have also been rarely linked to other types of cancer, including a type called breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Since the risk of developing BIA-ALCL is low, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not recommend removing textured breast implants or tissue expanders unless there are symptoms. Although these problems are very unusual, talk with your doctor about the risks.

Tissue flap procedures. These techniques use muscle and tissue from elsewhere in the body to reshape the breast. Tissue flap surgery may be done with a “pedicle flap,” which means tissue from the back or belly is moved to the chest without cutting the blood vessels. A “free flap” means the blood vessels are cut and the surgeon needs to attach the moved tissue to new blood vessels in the chest. There are several flap procedures:

-

Transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap. This method, which can be done as a pedicle flap or free flap, uses muscle and tissue from the lower stomach wall.

-

Latissimus dorsi flap. This pedicle flap method uses muscle and tissue from the upper back. Implants are often inserted during this flap procedure.

-

Deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap. The DIEP free flap takes tissue from the abdomen, and the surgeon attaches the blood vessels to the chest wall.

-

Gluteal free flap. The gluteal free flap uses tissue and muscle from the buttocks to create the breast, and the surgeon also attaches the blood vessels. Transverse upper gracilis (TUG), which uses tissue from the upper thigh, may also be an alternative.

Because blood vessels are involved with flap procedures, these strategies are usually not recommended for people with a history of diabetes or connective tissue or vascular disease, or for people who smoke, as the risk of problems during and after surgery is much higher.

The DIEP and other flap procedures take longer to perform in the operating room and have a longer recovery time following surgery. However, the appearance of the breast may be preferred, especially when radiation therapy is part of the treatment plan.

Talk with your doctor for more information about reconstruction options and a referral to a plastic surgeon. When considering a plastic surgeon, choose a doctor who has experience with a variety of reconstructive surgeries, including implants and flap procedures. They can discuss the pros and cons of each procedure.

External breast forms (prostheses)

An external breast prosthesis or artificial breast form provides an option for people who plan to delay or not have reconstructive surgery. These can be made of silicone or soft material, and they fit into a mastectomy bra. Breast prostheses can be made to provide a good fit and natural appearance. Read more about choosing a breast prosthesis.

Flat closure

Some people choose to have a flat closure, also called "going flat," after having a mastectomy instead of having breast reconstruction. This means the surgeon tightens and smooths out the remaining skin, fat, and tissue as much as possible so that the chest wall appears flat. However, a scar will remain.

If you choose to have a flat closure after mastectomy, it is important to go to a surgeon experienced in performing the procedure. Talk with your surgeon about your desired results and ask to see pictures of their work. If you’re not comfortable with the response you receive, consider getting a second opinion.

Deciding to go flat or have breast reconstruction is a personal choice. Each person needs to do what is best for them and choose what honors and respects their values and lifestyle. Learn more about going flat.

Summary of surgical options

To summarize, surgical treatment options include the following:

-

Removal of cancer in the breast: Lumpectomy or partial mastectomy, generally followed by radiation therapy if the cancer is invasive. Mastectomy may also be recommended, with or without immediate reconstruction.

-

Lymph node evaluation: Sentinel lymph node biopsy and/or axillary lymph node dissection.

You are encouraged to talk with your doctor about which surgical option is right for you. Also, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have and what should be reported to them.

More extensive surgery, such as a mastectomy, is not always better and may cause more complications. The combination of lumpectomy and radiation therapy has a slightly higher risk of the cancer coming back in the same breast or the surrounding area. However, the long-term survival of people who choose to have a lumpectomy is exactly the same as those who have a mastectomy. Even with a mastectomy, not all breast tissue can be removed, and there is still a chance of recurrence or of developing a new breast cancer.

People with a very high risk of developing a new cancer in the other breast may consider a bilateral mastectomy, meaning both breasts are removed. This includes people with BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations and people with cancer in both breasts. People with BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations should talk with their doctor about which surgical option might be best for them, as they have an increased risk of developing breast cancer in the opposite breast and of developing a new breast cancer in the same breast compared to those without these mutations. ASCO recommends that people with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation who are being treated with a mastectomy for the breast with cancer should also be offered a risk-reducing mastectomy for the opposite breast, including nipple-sparing mastectomy. This is because getting a risk-reducing mastectomy in the opposite breast is associated with a decreased risk of getting cancer in that breast. However, not everyone will be a good candidate for nipple-sparing mastectomy, either because of characteristics of their cancer or because of factors related to their breast anatomy. For example, people with large breasts and little nipple projection may need a breast reduction prior to undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy.

To assess your risk of developing cancer in the opposite breast and determine whether you might be eligible for a risk-reducing mastectomy, your doctor will consider several factors:

-

Age of diagnosis

-

Family history of breast cancer

-

The likelihood of recurrence of your breast cancer or other cancers you may have, such as ovarian cancer

-

Your ability to have regular surveillance studies, such as breast MRI, to look for breast cancer

-

Any other diseases or conditions you might have

-

Life expectancy

People with a moderate-risk gene mutation, like PALB2, CHEK2 or ATM, should also talk with their doctor and genetic counselor about their risk of developing breast cancer in the opposite breast and whether undergoing a risk-reducing mastectomy, including a nipple-sparing mastectomy, may be right for them.

People with a high-risk mutation who do not have a bilateral mastectomy should have regular screening of the remaining breast tissue with an annual mammogram and breast MRI for enhanced surveillance.

For people who are not at very high risk of developing a new cancer in the future, having a healthy breast removed in a bilateral mastectomy neither prevents cancer recurrence nor improves their survival. It also will not change the recommendation for treatment of the cancer with medications such as chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. Although the risk of getting a new cancer in that breast will be lowered, surgery to remove the other breast does not reduce the risk of the original cancer coming back. Survival is based on the prognosis of the initial cancer. In addition, more extensive surgery may be linked with a greater risk of problems. Read more about talking with your doctor about breast surgery options.

This information is based on ASCO’s recommendations for the management of hereditary breast cancer. Please note that this link takes you to a separate ASCO website.

Return to top

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. There are several different types of radiation therapy:

-

Whole breast irradiation. Whole breast irradiation is external-beam radiation therapy that is given to the entire breast. External-beam radiation therapy is the most common type of radiation treatment and is given from a machine outside the body. As described below, whole breast irradiation can be given using a number of different treatment schedules.

-

Partial breast irradiation.Partial breast irradiation (PBI) is radiation therapy that is given directly to the tumor area instead of the entire breast. It is more common after a lumpectomy. Targeting radiation directly to the tumor area usually shortens the amount of time that patients need to receive radiation therapy. However, only some patients may be able to have PBI. Although early results have been promising, PBI is still being studied. PBI can be given using external-beam or intra-operative radiation therapy or brachytherapy.

-

Intra-operative radiation therapy. This is when radiation treatment is given using a probe in the operating room.

-

Brachytherapy. This type of radiation therapy is given by placing radioactive sources into the tumor.

Although the research results are encouraging, intra-operative radiation therapy and brachytherapy are not widely used. Where available, they may be options for a patient with a small tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes. You may want to discuss with your radiation oncologist the pros and cons of PBI compared to whole breast radiation therapy.

-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is a more advanced way to give external-beam radiation therapy to the breast. The intensity of the radiation directed at the breast is varied to better target the tumor, spreading the radiation more evenly throughout the breast. The use of IMRT lessens the radiation dose and may decrease possible damage to nearby organs, such as the heart and lung, as well as lessen the risks of some immediate side effects, such as peeling of the skin during treatment. This can be especially important for people with medium to large breasts who have a higher risk of side effects, such as peeling and burns, compared with people with smaller breasts. IMRT may also help to lessen the long-term effects on the breast tissue, such as hardness, swelling, or discoloration, that were common with older radiation techniques.

IMRT is not recommended for everyone. Talk with your radiation oncologist to learn more. Special insurance approval may also be needed for coverage for IMRT. It is important to check with your health insurance company before any treatment begins to make sure it is covered.

-

Proton therapy. Standard radiation therapy for breast cancer uses x-rays, also called photon therapy, to kill cancer cells. Proton therapy is a type of external-beam radiation therapy that uses protons rather than x-rays. At high energy, protons can destroy cancer cells. Protons have different physical properties that may allow the radiation therapy to be more targeted than photon therapy and potentially reduce the radiation dose. The therapy may also reduce the amount of radiation that goes near the heart. Researchers are studying the benefits of proton therapy versus photon therapy in a national clinical trial. Currently, proton therapy is an experimental treatment and may not be widely available or covered by health insurance.

Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule (see below), usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time. Treatment is most often given once a day, 5 days a week, for 1 to 6 weeks. Radiation therapy often helps lower the risk of recurrence in the breast. In fact, with modern surgery and radiation therapy, recurrence rates in the breast are now less than 5% in the 10 years after treatment or 6% to 7% at 20 years. Survival is the same with lumpectomy or mastectomy. If there is cancer in the lymph nodes under the arm, radiation therapy may also be given to the same side of the neck or underarm near the breast or chest wall.

Radiation therapy may be given after or before surgery:

-

Adjuvant radiation therapy is given after surgery. Most patients who have a lumpectomy also have radiation therapy. Patients who have a mastectomy may or may not need radiation therapy, depending on the features of the tumor. Radiation therapy may be recommended after mastectomy if a patient has a larger tumor, cancer in the lymph nodes, cancer cells outside of the capsule of the lymph node, or cancer that has grown into the skin or chest wall, as well as for other reasons. When patients are also recommended to have adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy is usually given after chemotherapy is complete. Radiation therapy after surgery for DCIS may or may not be offered depending on the risk of recurrence.

-

Neoadjuvant radiation therapy is radiation therapy given before surgery to shrink a large tumor, which makes it easier to remove. This approach is uncommon and is usually only considered when a tumor cannot be removed with surgery.

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, including fatigue, swelling of the breast, redness and/or skin discoloration, and pain or burning in the skin where the radiation was directed, sometimes with blistering or peeling. Your doctor can recommend topical medication to apply to the skin to treat some of these side effects. Following radiation therapy, the breast can feel firmer or the skin of the breast can feel thicker.

Very rarely, a small amount of the lung can be affected by the radiation therapy, causing pneumonitis, a radiation-related swelling of the lung tissue. This risk depends on the size of the area that received radiation therapy, and it tends to heal with time.

In the past, with older equipment and radiation therapy techniques, people who received treatment for breast cancer on the left side of the body had a small increase in the long-term risk of heart disease. Modern techniques, such as respiratory gating, which uses technology to guide the delivery of radiation while a patient breathes, are now able to spare the vast majority of the heart from the effects of radiation therapy.

Many types of radiation therapy may be available to you with different schedules (see below). Talk with your doctor about the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Radiation therapy schedule

Radiation therapy is usually given daily for a set number of weeks.

-

After a lumpectomy. Radiation therapy after a lumpectomy is external-beam radiation therapy generally given Monday through Friday for 3 to 4 weeks if the cancer is not in the lymph nodes. If the cancer is in the lymph nodes, radiation therapy is often given for 5 to 6 weeks. However, these durations are changing, as there is a preference for a shorter duration to be given in patients who meet the criteria for shorter treatment. This often starts with radiation therapy to the whole breast, followed by a more focused treatment to where the tumor was located in the breast for the remaining treatments.

This focused part of the treatment, called a boost, is standard for most patients with invasive breast cancer to reduce the risk of a recurrence in the breast. People with DCIS may also receive the boost. For patients with a low risk of recurrence, the boost may be optional. It is important to discuss this treatment approach with your doctor.

-

After a mastectomy. For those who need radiation therapy after a mastectomy, it is usually given 5 days a week for 5 to 6 weeks. Radiation therapy can be given before or after reconstructive surgery. As is the case following lumpectomy, some patients may be recommended to have less than 5 weeks of radiation therapy after mastectomy.

Even shorter schedules have been studied and are in use in some centers, including accelerated partial breast radiation therapy for 5 days.

These shorter schedules may not be options for patients who need radiation therapy after a mastectomy or radiation therapy to their lymph nodes. Also, longer schedules of radiation therapy may be needed for some people.

Adjuvant radiation therapy concerns for older patients and/or those with a small tumor

Recent research studies have looked at the possibility of avoiding radiation therapy for people age 65 or older with an ER-positive, lymph node-negative, early-stage tumor (see Introduction), or for people with a small tumor. Importantly, these studies show that for people with small, less aggressive breast tumors that are removed with lumpectomy, the likelihood of cancer returning in the same breast is very low. Treatment with radiation therapy reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence in the same breast even further compared with surgery alone. However, radiation therapy does not lengthen a person's life.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) continue to recommend radiation therapy as the standard option after lumpectomy. However, they note that people with special situations or a low-risk tumor could reasonably choose not to have radiation therapy and use only systemic medication therapy (see below) after lumpectomy. This includes people age 70 or older, as well as those with medical conditions that could limit life expectancy within 5 years. People who choose this option will have a modest increase in the risk of the cancer coming back in the breast. It is important to discuss the pros and cons of omitting radiation therapy with your doctor.

Adjuvant radiation therapy for those with a genetic mutation

ASCO recommends that, when appropriate, adjuvant radiation therapy should be offered to people with breast cancer with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. People with a TP53 mutation are at higher risk of complications from radiation therapy, and therefore should undergo mastectomy instead of lumpectomy and radiation. Those with an ATM mutation or other related mutations should talk with their doctor about whether adjuvant radiation therapy is right for them. Currently, there is not enough data to recommend avoiding radiation therapy in all people with ATM mutations.

Return to top

Therapies using medication

The treatment plan may include medications to destroy cancer cells. Medication may be given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. When a drug is given this way, it is called systemic therapy. Medication may also be given locally, which is when the medication is applied directly to the cancer or kept in a single part of the body. However, this is almost never done in breast cancer treatment.

This treatment is generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication. Medications are often given through an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle, an injection into a muscle or under the skin, or as a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). If you are given oral medications, be sure to ask your health care team about how to safely store and handle them.

The types of medications used for breast cancer include:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Hormonal therapy

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunotherapy

Each of these therapies for treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer is discussed below in more detail. A person may receive 1 type of medication at a time or a combination of medications given at the same time. They can also be given as part of a treatment plan that includes surgery and/or radiation therapy. Different drugs or combinations of drugs are use to treat metastatic disease. Information about these therapies can be found in this website's Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Your doctor may suggest that you consider participating in clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat breast cancer. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purposes, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

It is also important to let your doctor know if you are taking any other prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements. Herbs, supplements, and other drugs can interact with cancer medications, causing unwanted side effects or reduced effectiveness. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells. It may be given before surgery to shrink a large tumor, make surgery easier, and/or reduce the risk of recurrence. When it is given before surgery, it is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. It may also be given after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence, called adjuvant chemotherapy.

A neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a combination of drugs given in a specific number of cycles over a set period of time. Chemotherapy may be given on many different schedules depending on what worked best in clinical trials for that specific type of regimen. It may be given once a week, once every 2 weeks, or once every 3 weeks. There are many types of chemotherapy used to treat breast cancer. Common drugs include the following, most of which are available as a generic drug:

-

Docetaxel

-

Paclitaxel

-

Doxorubicin

-

Epirubicin

-

Capecitabine

-

Carboplatin

-

Cyclophosphamide

-

Fluorouracil (5-FU)

-

Methotrexate

-

Protein-bound paclitaxel

A patient may receive 1 drug or a combination of different drugs given at the same time to treat their cancer. Research has shown that combinations of certain drugs are sometimes more effective than single drugs for adjuvant treatment.

The following drugs or combinations of drugs may be used as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer:

-

AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide)

-

EC (epirubicin, cyclophosphamide)

-

AC or EC followed by T (paclitaxel or docetaxel), or the reverse

-

AC or EC followed by T (paclitaxel or docetaxel) and carboplatin, or the reverse

-

CAF (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU)

-

CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-FU)

-

CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU)

-

TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide)

-

TC (docetaxel and cyclophosphamide)

-

Capecitabine (Xeloda)

Therapies that target the HER2 receptor may be given with chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer (see "Targeted therapy," below). An example is the antibody trastuzumab. Combination regimens for early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer may include:

-

AC-TH (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel or docetaxel, trastuzumab)

-

AC-THP (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel or docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

-

TCH (paclitaxel or docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab)

-

TCHP (paclitaxel or docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

-

TH (paclitaxel, trastuzumab)

Immunotherapies may be given with chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer (see "Immunotherapy," below). An example is the antibody pembrolizumab. Combination regimens for triple negative breast cancer may include:

-

TC/pembro-AC/pembro (paclitaxel and carboplatin plus pembrolizumab followed by doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide plus pembrolizumab)

-

TC/pembro-EC/pembro (paclitaxel and carboplatin plus pembrolizumab followed by epirubicin and cyclophosphamide plus pembrolizumab)

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual, the drug(s) used, whether the chemotherapy has been combined with other drugs, and the schedule and dose used. These side effects can include fatigue, risk of serious infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, diarrhea, constipation, numbness and tingling, pain, early menopause, weight gain, and chemo-brain or cognitive dysfunction. These side effects can often be very successfully prevented or managed during treatment with supportive medications, and they usually go away after treatment is finished. For some people, numbness and tingling can remain after chemotherapy. For hair loss reduction, talk with your doctor about whether the center does cold cap or scalp cooling techniques. Rarely, long-term side effects may occur, such as heart damage or secondary cancers such as leukemia or lymphoma.

Many patients feel well during chemotherapy and are active, including taking care of their families, working, and exercising during treatment, although each person’s experience can be different. Talk with your health care team about the possible side effects of your specific chemotherapy plan, and seek medical attention immediately if you experience a fever during chemotherapy.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy.

Return to top

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy, also called endocrine therapy, is an effective treatment for most tumors that test positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors (called ER positive or PR positive; see Introduction). This type of tumor uses hormones to fuel its growth. Blocking the hormones can help prevent a cancer recurrence and death from breast cancer when hormonal therapy is used either by itself or after chemotherapy.

Hormonal therapy for breast cancer treatment is different than menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). MHT may also be called postmenopausal hormone therapy or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Hormonal therapies used in breast cancer treatment act as “anti-hormone” or “anti-estrogen” therapies. They block hormone actions or lower hormone levels in the body. Hormonal therapy may also be called endocrine therapy. The endocrine system in the body makes hormones. Learn more about the basics of hormone therapy.

Hormonal therapy may be given before surgery to shrink a tumor, make surgery easier, and/or lower the risk of recurrence. This is called neoadjuvant hormonal therapy. When given before surgery, it is typically given for at least 3 to 6 months before surgery and continued after surgery. It may also be given solely after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence. This is called adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Types of hormonal therapy

-

Tamoxifen. Tamoxifen is a drug that blocks estrogen from binding to breast cancer cells. It is effective for lowering the risk of recurrence in the breast that had cancer, the risk of developing cancer in the other breast, and the risk of distant recurrence. Tamoxifen works in people who have been through menopause as well as those who have not.

Tamoxifen is a pill that is taken daily by mouth every day for 5 to 10 years. For premenopausal people, it may be combined with medication to stop the ovaries from producing estrogen. It is important to discuss any other medications or supplements you take with your doctor, as there are some that may interfere with tamoxifen. Common side effects of tamoxifen include hot flashes and vaginal dryness, discharge, or bleeding. Very rare risks include a cancer of the lining of the uterus, cataracts, and blood clots. However, tamoxifen may improve bone health and cholesterol levels in postmenopausal people.

-

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs). AIs decrease the amount of estrogen made in tissues other than the ovaries in post-menopausal people by blocking the aromatase enzyme. This enzyme changes weak male hormones called androgens into estrogen. These drugs include anastrozole (Arimidex), exemestane (Aromasin), and letrozole (Femara). All of the AIs are pills taken daily by mouth. Only patients who have gone through menopause or who take medicines to stop the ovaries from making estrogen (see "Ovarian suppression," below) can take AIs. Treatment with AIs, either as the first hormonal therapy taken or after treatment with tamoxifen, may be more effective than taking only tamoxifen to reduce the risk of recurrence in post-menopausal people.

The side effects of AIs may include muscle and joint pain, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, an increased risk of osteoporosis and broken bones, and rarely, increased cholesterol levels and thinning of hair. Research shows that all AIs work equally well and have similar side effects. However, people who have undesirable side effects while taking one AI medication may have fewer side effects with a different AI for unclear reasons.

Patients who have not gone through menopause and who are not getting shots to stop the ovaries from working (see below) should not take AIs, as they do not block the effects of estrogen made by the ovaries. Often, doctors will monitor blood estrogen levels in people whose menstrual cycles have recently stopped, those whose periods stopped with chemotherapy, or those who have had a hysterectomy but their ovaries are still in place, to be sure that the ovaries are no longer producing estrogen.

-

Ovarian suppression or ablation. Ovarian suppression is the use of drugs to stop the ovaries from producing estrogen. Ovarian ablation is the use of surgery to remove the ovaries. These options may be used in addition to another type of hormonal therapy for people who have not been through menopause.

-

For ovarian suppression, gonadotropin or luteinizing releasing hormone (GnRH or LHRH) agonist drugs are used to stop the ovaries from making estrogen, causing temporary menopause. Goserelin (Zoladex) and leuprolide (Eligard, Lupron) are types of these drugs. They are typically given in combination with other hormonal therapy, not alone. They are given by injection every 4 or 12 weeks and stop the ovaries from making estrogen. The effects of GnRH drugs go away if treatment is stopped.

-

For ovarian ablation, surgery to remove the ovaries is used to stop estrogen production. While this is permanent, it can be a good option for people who no longer want to become pregnant to consider. The cost is typically lower over the long term.

Hormonal therapy after menopause

People who have gone through menopause and are prescribed hormonal therapy have several options:

-

Tamoxifen for 5 to 10 years

-

An AI for 5 to 10 years

-

Tamoxifen for 5 years, followed by an AI for up to 5 years. This would be a total of 10 years of hormonal therapy.

-

Tamoxifen for 2 to 3 years, followed by 2 to 8 years of an AI for a total of 5 to 10 years of hormonal therapy.

In general, patients should expect 5 to 10 years of hormonal therapy. The tumor biomarkers and other features of the cancer may also impact who is recommended to take a longer course of hormonal therapy.

Hormonal therapy before menopause

As noted above, premenopausal patients should not take AI medications without ovarian suppression, as they will not lower estrogen levels. Options for adjuvant hormonal therapy for premenopausal people include the following:

-

Tamoxifen for 5 years. Then, treatment is based on their risk of cancer recurrence as well as whether or not they have gone through menopause during those first 5 years.

-

If a person has not gone through menopause after the first 5 years of treatment and is recommended to continue treatment, they can continue tamoxifen for another 5 years, for a total of 10 years of tamoxifen. Alternatively, a person could start ovarian suppression and switch to taking an AI for another 5 years.

-

If a person goes through menopause during the first 5 years of treatment and is recommended to continue treatment, they can continue tamoxifen for an additional 5 years or switch to an AI for 5 more years. This would be a total of 10 years of hormonal therapy. Only people who are clearly post-menopausal should consider taking an AI.

-

Some patients are recommended to stop all hormonal therapy treatment after the first 5 years of tamoxifen.

-

Ovarian suppression for 5 years along with additional hormonal therapy, such as tamoxifen or an AI, may be recommended in the following situations, depending on a person’s age and risk of recurrence:

-

For people who are diagnosed with breast cancer at a very young age.

-

For people who have a high risk of cancer recurrence.

-

For people with stage II or stage III cancer when chemotherapy is also recommended. However, evidence now suggests benefits independent of the use of chemotherapy as well.

-

For people with stage I or stage II cancer with a higher risk of recurrence who may consider also having chemotherapy.

-

For people who cannot take tamoxifen for other health reasons, such as having a history of blood clots. They would take an AI medication in addition to ovarian suppression.

-

Ovarian suppression is not recommended in addition to another type of hormonal therapy in the following situations:

Additional targeted therapy in combination with hormone therapy

The following drug is used in combination with hormonal therapy for the treatment of non-metastatic hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer and a high risk of breast cancer recurrence.

-

Abemaciclib (Verzenio). This oral drug, called a CDK4/6 inhibitor, targets a protein in breast cancer cells called CDK4/6, which may stimulate cancer cell growth. It is approved as treatment in combination with hormonal therapy (tamoxifen or an AI) to treat people with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early breast cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes and has a high risk of recurrence. It can cause diarrhea, low blood count, fatigue, and other symptoms. ASCO recommends consideration of 2 years of treatment with abemaciclib combined with 5 or more years of hormonal therapy for patients meeting these criteria, including for people whose cancer has a Ki-67 score higher than 20% (see Diagnosis).

This information is based on ASCO recommendations for adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Please note this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Hormonal therapy for treatment of metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer is described in the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

Learn more about the basics of hormonal therapy.

Return to top

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. These treatments are very focused and work differently than chemotherapy. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells and limits damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in your tumor. In addition, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

The first approved targeted therapies for breast cancer were hormonal therapies. Then, HER2-targeted therapies were approved to treat HER2-positive breast cancer.

HER2-targeted therapy

-

Trastuzumab (FDA-approved biosimilar forms are available). This drug is approved as a therapy for non-metastatic, HER2-positive breast cancer. It is given either as an infusion into a vein every 1 to 3 weeks or as an injection into the skin every 3 weeks. Currently, patients with stage I to stage III breast cancer (see Stages) should receive a trastuzumab-based regimen, often including a combination of trastuzumab with chemotherapy, followed by a total of 1 year of adjuvant HER2-targeted therapy. Patients receiving trastuzumab have a small (2% to 5%) risk of heart problems. This risk is increased if a patient has other risk factors for heart disease or receives chemotherapy that also increases the risk of heart problems at the same time. These heart problems may go away and can be treated with medication.

-

Pertuzumab (Perjeta). This drug is approved for stage II and III breast cancer in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy. It is given as an infusion into a vein every 3 weeks.

-

Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and hyaluronidase–zzxf (Phesgo). This combination drug, which contains pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and hyaluronidase-zzxf in a single dose, is approved for people with early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer. It may be given in combination with chemotherapy. It is given by injection under the skin and can be administered either at a treatment center or at home by a health care professional.

-

Neratinib (Nerlynx). This oral drug is approved as a treatment for higher-risk HER2-positive, early-stage breast cancer. It is taken for a year, starting after patients have finished 1 year of trastuzumab.

-

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine or T-DM1 (Kadcyla). This is approved for patients with early-stage breast cancer who have had treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy with either paclitaxel or docetaxel followed by surgery, and who had cancer remaining (or present) at the time of surgery. ASCO recommends that these patients receive 14 cycles of T-DM1 after surgery unless the cancer recurs or the side effects from T-DM1 become too difficult to manage. T-DM1 is a combination of trastuzumab linked to a very small amount of a strong chemotherapy. This allows the drug to deliver chemotherapy into the cancer cell while lessening the chemotherapy received by healthy cells, which usually means that it causes fewer side effects than standard chemotherapy. T-DM1 is given by vein every 3 weeks.

This information is based on the ASCO guideline, “Selection of Optimal Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy for Early Breast Cancer.” Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects of specific medications and how they can be managed.

Bone modifying drugs

Bone modifying drugs block bone destruction and help strengthen the bone. These medications, called bisphosphonates, may also be used to prevent cancer from recurring in the bone. Bone modifying drugs are not a substitute for standard anti-cancer treatments. Certain types of bone modifying drugs are also used in low doses to prevent and treat osteoporosis, which is the thinning of the bones.

All people with breast cancer who have been through menopause, regardless of the cancer’s hormone receptor status and HER2 status, should have a discussion with their doctor whether bisphosphonates are right for them. Several factors affect this decision, including your risk of recurrence, the side effects of treatment, the cost of treatment, your preferences, and your overall health.

If treatment with bisphosphonates is recommended, ASCO recommends starting within 3 months after surgery or within 2 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. This may include treatment with clodronate (multiple brand names), ibandronate (Boniva), or zoledronic acid (Zometa). Clodronate is not available in the United States.

This information is based on the ASCO and Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) guideline, “Use of Adjuvant Bisphosphonates and Other Bone-Modifying Agents in Breast Cancer.” Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Other types of targeted therapy for breast cancer

You may have other targeted therapy options for breast cancer treatment, depending on several factors. The following drug is used for the treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer in people with an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation and a high risk of breast cancer recurrence.

-

Olaparib (Lynparza). This is a type of oral drug called a PARP inhibitor, which destroys cancer cells by preventing them from fixing damage to the cells. ASCO recommends using olaparib to treat early-stage, HER2-negative breast cancer in people with an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation and a high risk of breast cancer recurrence. Adjuvant olaparib should be given for 1 year following the completion of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy (if needed).

You can learn more about drugs used to treat metastatic breast cancer in the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

Return to top

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body's natural defenses to fight cancer by improving your immune system’s ability to attack cancer cells. The following drug, which is a type of immunotherapy called an immune checkpoint inhibitor, is used for the treatment of high-risk, early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer.

-

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This is a type of immunotherapy that is approved by the FDA to treat high-risk, early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer in combination with chemotherapy before surgery. It is then continued following surgery for 9 doses.

Common side effects include skin rashes, flu-like symptoms, thyroid problems, diarrhea, and weight changes. Other severe but less common side effects can also occur. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects of the immunotherapy recommended for you and what can be done to watch for and manage them. Learn more about the basics of immunotherapy.

Return to top

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy for non-metastatic breast cancer

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy is treatment given before surgery to shrink a large tumor and/or reduce the risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or targeted therapy may all be given as neoadjuvant treatments for people with certain types of breast cancer.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, for example, is the treatment usually recommended for people with inflammatory breast cancer. It is also the treatment recommended for people with locally advanced cancer (large tumor(s) and/or several lymph nodes affected) or cancer that would be difficult to remove with surgery at the time of diagnosis but may become removable with surgery after receiving neoadjuvant treatment. The doctor will consider several factors, including the type of breast cancer that you have, such as its grade, stage, and estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 status, to guide their recommendation around whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be part of your treatment plan.

ASCO recommends that neoadjuvant systemic therapy be offered to people with high-risk HER2-positive breast cancer or to people with triple-negative breast cancer who would then receive additional drug therapy after surgery if cancer still remains. Neoadjuvant therapy may also be offered to reduce the amount of surgery that needs to be performed and allow someone who would otherwise require a mastectomy, for example, to consider having a lumpectomy.

In situations where delaying surgery is preferred (such as waiting for genetic test results to guide further treatment options or to allow time for deciding on breast reconstruction options), neoadjuvant systemic therapy may be offered.

People receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be monitored for the cancer’s response to treatment through regular examinations. Your doctor will likely suggest breast imaging after treatment for surgical planning. They may also perform imaging if they are concerned that the cancer may have progressed despite treatment. Your doctor will likely use the same type of imaging test in your follow-up care that was most helpful at the time your breast cancer was originally diagnosed. In general, it is not recommended that blood tests or biopsies be used to monitor response to therapy for people receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy options by type of non-metastatic breast cancer

For triple-negative breast cancer:

For patients with triple-negative breast cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes and/or is more than 1 centimeter (cm) in size, ASCO recommends they be offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Additional drugs, including the chemotherapy drug carboplatin and the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab (see above), may also be recommended in addition to usual chemotherapy drugs to increase the likelihood of having a complete response and reduce the risk of cancer returning. A complete response is when there is no cancer found in the tissue when it is removed during surgery. Talk with your doctor about the potential benefits and risks of receiving carboplatin and pembrolizumab before surgery.

People with early-stage (1 cm or less, and no lymph nodes that look abnormal) triple-negative breast cancer should not routinely be offered neoadjuvant therapy unless they are participating in a clinical trial.

For HER2-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer:

In cases where a recommendation for chemotherapy can be made without having all the information that is obtained from surgery, such as the actual size of the tumor or the number of involved lymph nodes, any person with HER2-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer can receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy instead of adjuvant chemotherapy. Meanwhile, for postmenopausal people with large tumors or other reasons why surgery may not be a good option at the time of diagnosis of the cancer, hormonal therapy with an aromatase inhibitor may be offered to reduce the size of the tumor. It may also be used to control the cancer if there is no role for surgery. However, hormonal therapy should not be routinely offered in this situation outside of a clinical trial for premenopausal people with early-stage HER2-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

For HER2-positive breast cancer:

For patients with HER2-positive breast cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes or is more than 2 cm in size, neoadjuvant therapy with chemotherapy in combination with the targeted therapy drug trastuzumab should be offered. Another targeted therapy drug against HER2, pertuzumab, may also be used with trastuzumab when given before surgery. However, people with early stage (1 cm or smaller and no abnormal appearing lymph nodes), HER2-positive cancer should not be routinely offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or drugs that target HER2 (such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab) outside of a clinical trial.

This information is based on the ASCO guideline, “Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Endocrine Therapy, and Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer.” Please note that this link takes you to another ASCO website.

Return to top

Systemic therapy concerns for people age 65 or older

Age should never be the only factor used to determine treatment options. Systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy, often work as well for older patients as they do for younger patients. However, older patients may be more likely to have side effects that impact their quality of life. Older patients may also have a higher risk of drug-associated toxicities.

For example, older patients may have a higher risk of developing heart problems from trastuzumab. This is more common for patients who already have heart disease and for those who receive certain combinations of chemotherapy. For older patients receiving chemotherapy, they may have a higher risk of fatigue and peripheral neuropathy. Learn more in this separate article on this website.

It is important for all patients to talk with their doctors about the systemic therapy options being recommended, including the benefits and risks. They should also ask about potential side effects and how they can be managed. Learn more about cancer and aging.

Return to top

Physical, emotional, and social effects of cancer (updated 08/2023)

In general, cancer and its treatment cause physical symptoms and side effects, as well as emotional, social, and financial effects. Managing all of these effects is called palliative care or supportive care. It is an important part of your care that is included along with treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer.

Supportive care focuses on improving how you feel during treatment by managing symptoms and supporting patients and their families with other, non-medical needs. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive this type of care. And it often works best when it is started right after a cancer diagnosis. People who receive supportive care along with treatment for the cancer often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report that they are more satisfied with treatment.

Supportive care treatments vary widely and often include medication, nutritional changes, relaxation techniques, emotional and spiritual support, and other therapies.

Research has shown that some integrative or complementary therapies may be helpful to manage symptoms and side effects. Integrative medicine is the combined use of medical treatment for the cancer along with complementary therapies, such as mind-body practices, natural products, and/or lifestyle changes. However, most natural products are unregulated, so the risk of them interacting with your treatment and causing harm is uncertain.

ASCO agrees with recommendations from the Society for Integrative Oncology (SIO) on several complementary options to help manage general side effects during and after breast cancer treatment. These include:

-

Music therapy, mindfulness meditation, stress management, and yoga for reducing stress

-

Mindfulness meditation and yoga to improve general quality of life

-

Acupressure and acupuncture to help with nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy

Specifically for managing anxiety and depression, ASCO and SIO recommend several complementary options to help manage these side effects during and after breast cancer treatment. These include the following for helping with anxiety or depression symptoms:

-

For reducing anxiety during breast cancer treatment: mind-body techniques like deep breathing, mindfulness meditation practices, yoga, hypnosis, music therapy, reflexology, and lavender essential oil

-

For reducing anxiety after breast cancer treatment: mindfulness-based stress reduction meditation practices, acupuncture, tai chi, qigong, and reflexology

-

For reducing symptoms of depression during breast cancer treatment: mindfulness-based stress reduction meditation practices, yoga, music therapy, relaxation techniques like deep breathing, and reflexology

-

For reducing symptoms of depression after breast cancer treatment: mindfulness meditation practices, yoga, tai chi, and qigong

There are other techniques or practices that may help reduce anxiety or symptoms of depression during or after cancer. However, there are no specific recommendations for them, so be sure to talk with your health care team about whether any additional techniques may be helpful for you.

Learn more about the recommendations for using integrative therapy for breast cancer from an SIO guideline and from a joint SIO-ASCO guideline. (Note that these links will take you to different ASCO websites.)

People may have concerns about if or how their treatment may affect their sexual health and their ability to have children in the future, called fertility. People are encouraged to talk with their health care team about these topics prior to starting treatment.

Before treatment begins, talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment in the recommended treatment plan. You should also talk about the possible side effects of the specific treatment plan and symptom management options. Many people also benefit from talking with a social worker and participating in support groups. Ask your doctor about these resources, too.

During treatment, your health care team may ask you to answer questions about your symptoms and side effects and to describe each problem. Be sure to tell the health care team if you are experiencing a problem. This helps the health care team treat any symptoms and side effects as quickly as possible. It can also help prevent more serious problems in the future.

Learn more about the importance of tracking side effects in another part of this guide. Learn more about supportive care or palliative care in a separate section of this website.

Return to top

Recurrent breast cancer

If the cancer returns after treatment for early-stage disease, it is called recurrent cancer. When breast cancer recurs, it may come back in the following parts of the body:

-

The same place as the original cancer. This is called a local recurrence.

-

The chest wall or lymph nodes under the arm or in the chest on the same side as the original cancer. This is called a regional recurrence.

-

Another place, including distant organs such as the bones, lungs, liver, and brain. This is called a distant recurrence or a metastatic recurrence. For more information on a metastatic recurrence, see the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

If a recurrence happens, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about it. Testing may include imaging tests, such as those discussed in the Diagnosis section. In addition, another biopsy will likely be needed to confirm the breast cancer recurrence and learn about the features of the cancer.

After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about the treatment options. The treatment plan may include the treatments described above, such as surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and hormonal therapy. They may be used in a different combination or given at a different pace. The treatment options for recurrent breast cancer depend on the following factors:

-

Previous treatment(s) for the cancer first diagnosed

-

Time since the first diagnosis

-

Location of the recurrence

-

Characteristics of the tumor, such as ER, PR, and HER2 status

-

Results from previous genomic tests

-

Depending on the type of breast cancer, your doctor may recommend testing for the following molecular features:

-

PD-L1. PD-L1 is found on the surface of cancer cells and some of the body's immune cells. This protein stops the body’s immune cells from destroying the cancer, especially in triple-negative breast cancer.

-

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). Tumors that have MSI-H or dMMR have difficulty repairing damage to their DNA. This means that they develop many mutations or changes. These changes make abnormal proteins on the tumor cells that make it easier for immune cells to find and attack the tumor.

-

NTRK gene fusions. This is a specific genetic change found in a range of cancers, including breast cancer.

-

PI3KCA gene mutation. This is a specific genetic change commonly found in breast cancer.

People with recurrent breast cancer sometimes experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. You are encouraged to talk with your health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help you cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Treatment options for a local or regional breast cancer recurrence

A local or regional recurrence is often manageable and may be curable. The treatment options are explained below:

-

For people with a local recurrence in the breast after initial treatment with lumpectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy, the recommended treatment is usually a mastectomy. The cancer is usually completely removed with this treatment.

-

For people with a local or regional recurrence in the chest wall after an initial mastectomy, surgical removal of the recurrence followed by radiation therapy to the chest wall and lymph nodes is the recommended treatment. However, if radiation therapy has already been given for the initial cancer, this may not be an option. Radiation therapy cannot usually be given at full dose to the same area more than once. Sometimes, systemic therapy is given before surgery to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove.

-

Other treatments used to reduce the chance of a future distant recurrence include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapy. These are used depending on the tumor and the type of treatment previously received.

Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat recurrent breast cancer.

Return to top

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with breast cancer. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.